Johnny Greenwood writes: During the Coronavirus lock down of spring 2020, I asked my mum to begin her memoirs. She was living at her house in Great Hinton, Wiltshire and unable to go out. She began writing immediately – and quickly delivered around 20 pages. I’ve begun adding some photographs.

I was born in February 1942. During that month Singapore fell to the Japanese, arguably the most devastating defeat in British military history. I was born in Corbridge on Tyne, a name which it is very difficult to fit into the spaces on forms like passport applications. We were up in the north because it was thought that Hitler might invade in the north east, and my father was a major in the Royal Artillery and was defending the coast. I have no memories of this time, though I do know that my grandmother was present at my christening.

My parents then moved to Mayfield in Sussex, as my father was in the army manning a large gun, a ‘Bochbuster’ howitzer. This was a huge gun on railway tracks which could be moved along the coast. I can just remember the house in Mayfield, though when I went to look for it many years later it seemed to have been pulled down to make a new road. My grandmother was still living with us and I have strong memories of her, and also many memories of her later in my childhood. On one occasion she won my teddy bear for me in the village fete raffle. ‘I shall win that teddy for Gill’ she said, and she did, although she only bought one ticket. It was a triumph, as toys were impossible to buy at that time, as all the factories were making materials for the war effort. My father made me several toys, which I wish I still had. One was a push along dog on wheels. The best was a dolls house which was an exact replica of the Mayfield house. My father copied all the furniture in exact detail, and he also made some water colour pictures for the walls, which were copies of illustrations for ‘Alice in Wonderland’. My father was a very good artist, and I am devastated that the dolls house and all the contents were thrown onto the tip many years later after it had been cherished by the family for a long time.

Next door to the Mayfield house was a hay field, and I can remember the farmer and a labourer coming with a huge cart horse and a cart to take away the hay. They loaded the hay onto the cart with pitchforks.

Food was hard to come by in 1942. One of my earliest memories is of sitting in my highchair while my mother tried to feed me sour plums. She later told me that this was because there was no sugar, and the plums were all she had to feed me with. My grandmother was a keen gardener and grew vegetables to help with the food shortage. There were no garden chemicals at that time, like weed killer, and so each individual caterpillar had to be taken off the cabbage leaves by hand. My grandmother used to take a jam jar with a string handle, fill it with boiling water, and drop the caterpillars in to kill them. I was made to help.

Is it possible that I have a memory from when I was only two? If it is, then I remember the convoys of troops and armaments moving past our house to the coast to get ready for the D Day landings in June 1944. It is a strong memory because the convoy was so long and so tightly packed that we couldn’t get out of our front gate onto the main road.

While we were living at Mayfield my twin brothers were born. Surprisingly I have no memory of this at all. My mother managed to find a lovely Scottish nanny, in spite of the war – you might have thought she would have preferred to be in the Wrens – who stayed with us while the twins were babies. I can still remember her singing songs from the highlands, like Annie Laurie, I’ll take the high road and you take the low road, etc.

In 1946 after the end of the war, my father took a new job at the Small Arms Factory in Enfield and we had to move house, leaving the Mayfield house which was rented and moving into Moffats. Moffats was a large house which had been divided into three parts, probably to help with the housing shortage after the war. My parents bought the largest part, one end of it, which also had an extensive garden. It had been divided very inexpertly, so that, for example, corridors ended in a brick wall. Moffats played a large part in my childhood and deserves a full description.

Moffats was a lovely mellow brick building. It consisted of a porch leading into a very large hall with a beautiful oak polished floor. At the end of the hall farthest from the front door there was a large tall bookcase. I think my love of reading may have started here as I could browse as much as I liked. I remember reading books about astronomy, and also an illustrated Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. There was a cupboard which contained leather bound copies of all the Ordnance Survey maps, which I think my father had ‘acquired’ during the war. Unfortunately, the lavatory above it leaked, and on one occasion someone opened the cupboard to find enormous mushroom-like funguses had grown all over the maps. The house had a lovely spiral wooden staircase said to have been used by Thomas More which went up three floors and ended in a glass atrium which often leaked in the rain. To the left as you went into the house was my father’s workshop. He had this built on when we moved in and you would never be allowed to do that now, as I’m sure now Moffats would be listed. However, my father filled his workshop with tools and lathes, and he made things there all the time. He even made a clock, a sort of grandmother clock, which worked by metal balls falling down a shoot. I wish I knew where that clock is now. My father used to pay me sometimes to help him in the workshop and to tidy it. There was also a downstairs loo. On the right of the hall was the dining room. It had a large round dining table which my father had copied for the doll’s house. It had beautiful dining chairs and a lovely view over the garden, but it had no heating except a small elewash house, which was in the hall. There was a kind of cupboard with a flap down door, and my mother used to collect the paper bags from the shopping and keep them in there, to use for packed lunches. It also had a lazy susan to dry the washing. A rich friend of my mother’s gave her an automatic washing machine after a year or two at Moffats, but before that all the washing, including sheets, was washed by hand and hung on the lazy susan to dry. The whole kitchen floor would be awash and my poor mother mopped it up time and time again.

On the left of the hall was the drawing room. It had a green carpet which was either said to have been intended for the railway, or to have come from my grandmother’s flat in Clapham which was bombed out. I’ve no idea which is true. There was a sofa and two armchairs upholstered in green, my father’s and my mother’s desks, and various bookshelves, made by my father. There was a very large water colour painting of some silver birch trees by a lake, which my father loved. The room had a bay window with window seats, and under the seats were many, many copies of old Punch magazines. You could close off the draughty bay window by pulling across some metal shutters, which my parents called ‘the iron curtain’, a reference to Winston Churchill’s speech in which he said that the communists had drawn an iron curtain across Europe to divide communist Europe from the West. There was also a radiogram. This came from the business my father ran between the wars, which was called Radiosetz Ltd, and which manufactured radios and radiograms. The company used to actually install radiograms in people’s houses, and we had a very pretty snuff box which had apparently been given to my father when he installed one in Plas Newydd on Anglesea, owned by the Marquess of Anglesey. It was a pity that Radiosetz never made much money.

On the first floor there were three bedrooms. The first one was mine, which was not very special, except that at some point I acquired a crystal set, a kind of primitive radio with headphones. I used to listen to Children’s Hour serials avidly, especially one called ‘After Sedgemoor’. On one occasion I had measles, and the doctor came to see me. The last episode of After Sedgemoor was in full swing, and I refused to stop listening. Sedgemoor was the final battle of the Monmouth rebellion, and the losing side were cruelly treated by Judge Jeffreys at the Bloody Assizes. I was on the side of the Duke of Monmouth.

Next came the twins’ nursery, which was special because it had a gas fire, and was the only warm room in the house. We played in there endlessly, roller skating on the lino floor and re-organising the dolls’ house. At some point we were given a rocking horse, which we still have, and I spent hours hairdressing its mane and tail. We did quite a lot of fighting.

At the end of the corridor was the family bathroom, and then, up some steps, my parents’ bedroom and bathroom. This bedroom had a balcony, though not one that was ever used as such, and also an awning. The awning had shredded years before, but the roller was still there. Every year some sparrows used to try to nest on it. They would build energetically to a certain point, but when the nest got too heavy the roller would rotate and the nests would fall off. My mother swore she could hear the birds swearing. There was a stunning view. My parents were keen listeners to the radio, and on Sunday evenings they use to listen to ‘Palm Court Orchestra’. My mother also loved ‘Music while you Work’ and ‘Mrs Dale’s Diary’, which was a kind of radio soap opera about a doctor’s wife. I have strong memories of coming in from school and finding my mother listening to Mrs Dale.

You could then go up stairs again to some more bedrooms. There was one which I think must have been used by Nanny, one belonging to my oldest brother Peter, and then my grandmother’s bedroom and sitting room. One of these two rooms was actually above the house next door, though the family next door couldn’t use it because there was no staircase from their part of the house. (Later they asked for it back, and my grandmother had to vacate it). The two rooms were a bedroom with a wash basin, and then, through that, a really cosy sitting room with a gas fire. (how would Granny have got out if there had been a fire?) The sitting room had a curtain across it half way, which we used to use for play acting. There was no bathroom, which must have given my granny a lot of inconvenience. From one small window you could see St Alban’s Abbey, which was miles away, but the window was high up. We had such fun with my Granny. When we came in from school we used to listen to the radio with her, Children’s hour again, Larry the Lamb, Jennings and Derbyshire, the serial etc etc. We loved it. Granny also did crafty things with us and some of the things we made for my mother were still extant until quite recently. Granny used to babysit, but as she was a long way from the nursery and very deaf, it was really nominal.

Outside was of course the garden, which was supremely important to my father. It was a wreck when we arrived, as the house had been, according to your belief, either a school or an orphanage during the war. My father took the whole thing in hand until it was a showcase. It consisted of a lawn, a rose garden, a heather garden, a herbaceous border, a bank covered in thousands of daffodils, an orchard. a large vegetable garden, rhododendrons, azaleas, a ha-ha, espalier apple trees and so on. None of this was there when we arrived. As you went into the drive there was a large rhododendron bush which had pink flowers which I used to play with endlessly, making them into all kinds of arrangements. When we first arrived, I used to play underneath the bush, and my father felt guilty when he destroyed my camp and transformed it into garden. After some time, my father and my brother Peter decided that the end of the main lawn would make a good grass tennis court. They got out the encyclopedia of sports games and pastimes to find out the correct dimensions. I remember so strongly Peter taking a garden fork and stabbing it into the grass where the first corner should be. There was a clanging noise, and Peter forked up an L-shaped piece of white metal, which was of course one of the markers for a tennis court. We had chosen exactly the same spot for our court as had some previous pre-war residents. After the court was finished my brothers and I had tennis lessons, and tennis parties were a frequent source of entertainment.

Down one end of the garden there was a big oak tree, which had a swing on one branch. When Peter was at home from the army, he used to entertain the twins and me, often rather vigorously. He used, for example, to sit on the swing with one of us on his shoulders. He would swing high, and then jump off the swing over the ha-ha with us still holding onto him. Very dangerous!

When I was about seven we bought a dog, which nominally belonged to me. It was a male fox terrier called Bundle. He was a very feral dog with huge sexual appetites, and he used to roam the countryside looking for bitches on heat. After we had had numerous phone calls telling us to come and collect him my father put some trellis across the gap between the house and the garage to make a fenced in yard. Bundle just climbed up and over, and was off again. He was a very selfish dog, who always fought and scrabbled to be the first person out of the car. None the less we all loved him, and he lived until after my father died.

Outside the garden beyond our land there was a large field with a lake at the bottom. The legend was that the lake was ornamental and had belonged to a substantial house called Gobions which had burned down. In the middle of the lake was a small island which had periwinkles growing on it. The twins and I yearned to reach the island, and at last we did, by making a raft out of empty oil drums, some planks and some rope. I can’t remember what my mother thought when I made her take me to a garage to ask for the oil drums. On one occasion the lake froze over enough for skating. People from the area drove down the field and shone their headlights on the frozen water. I had skates because I could use my mother’s, as by that time our feet were the same size. I did the best skating I could round the lake, but unfortunately someone skated over a twig, fell over backwards, cracked their head and became unconscious. An ambulance came, but the fun had gone out of the evening and everyone went home to bed.

We children were outside all summer playing. On the side of the house was a bell hanging, and when it was a mealtime my mother would ring the bell for us to come home. No one seemed to worry about where we were or what we were doing.

As always for children Christmas was special. My father’s birthday was December 23rd, and he made my mother, every year, make him a celebratory dinner of roast pheasant with all the trimmings. How could he do that when two days later she had to cook the meal of the century, for three adults, Peter and three children? In those days there were few if any kitchen gadgets. My mother made breadcrumbs for bread sauce by hand. She roasted chestnuts, pealed them, sieved them and used them for chestnut stuffing. Several weeks earlier she would have made the Christmas pudding, and we still have and use the same recipe. In those days there were always silver sixpences in the pudding, with a button which, if it turned up in your helping, was a ‘bachelor’s button’. I was lucky enough to have a rich godfather, who always sent glamorous presents. Once I received a lovely red leather writing case, which I took with me when I eventually went to boarding school. When we woke up on Christmas morning we would hear a scratchy sound, which was the coarse wool of one of my father’s shooting socks rubbing against the bedclothes with our stocking presents from Father Christmas inside. As we had such a large hall, we were able to have a very tall Christmas tree, which was put up on Christmas eve. My father made the lights for the tree, which were quite clumsy compared to today’s, though in those days they were a rarity.

The first winter we were at Moffats was 1946-47. It was notoriously extremely cold. Large drifts of snow blocked roads and railways, and caused problems transporting coal to the power stations. Power stations shut down and there were restrictions to people’s use of electricity. Coal was scarce. Vegetables froze to the ground, and it was hard to get the food you needed. My twin brothers were still babies and needed formula milk, which was also in short supply, and my father drove round the countryside searching for tins. The milk which the milkman managed to deliver froze in the bottles before we brought it in, and round tubes of frozen milk stuck out of the top. Europe suffered too, and my mother used to send parcels to ‘displaced persons’, who were part of the seven to eleven million people displaced by the war and homeless on the continent. She or Nanny washed the twins’ nappies, but when my mother hung them on the washing line they simply froze and came inside like stiff boards.

Early School Days

My first school was a little dame school above a shop in Brookmans Park. I’m not sure what you would call Brookmans Park then. It was not a pretty village, nor yet a small town. It grew up when the railway came in the 1920s and grew larger in the 1930s. It had a circular shopping area with a green in the middle and the Brookmans Park Hotel at one end. (now it is a very expensive area) My school was above the draper’s and haberdashers shop, and though I remember almost nothing of what I learned at the school, though I suppose I learned to read and write, I do remember loving the racks of coloured cotton reels in the shop downstairs. The centre of Brookmans Park was a good twenty minutes’ walk from our house, down a very bumpy potholed lane. My father drove our only car to work each day, so my mother had to walk me to school and back. No wonder no one was fat in those days.

The Brookmans Park school didn’t last long, and I next went to a small all girls’ prep school called Stormont, in Potters Bar. It still exists and from the website seems to be flourishing. Potters Bar was nearer into London than Brookmans Park and I used to get a bus there. Again, I don’t remember much about that school, in spite of the fact that I was there until I was eleven. I do think that my failings in maths stem from one particular teacher though. I can still see her giving out rulers, compasses and protractors, while having a foul runny cold, and in my mind getting snot all over our new equipment. But one lesson I loved was handwriting. We had textbooks called Marion Richardson writing patterns. There were patterns to copy, but my favourite was the poems. ‘They shut the way through the woods seventy years ago…’ and ‘Time, you old gypsy man, will you not stay, put up your caravan just for one day….’ I can still recite that last one, and who knows, maybe those poems lead on to my degree in English.

It was at Stormont that I met and became friends with Theresa Verschoyle, whose brother much later became my husband.

Riding

As a child I was a keen though not very good rider. I used to have a lesson every Saturday morning at a riding school not far away, and it was my only hobby. Along with other comics I took a riding magazine, and spent hours cutting out pictures of famous show jumpers and their horses. Around this time my father went to America on business, and the whole family listened avidly to his stories about New York, but I was most fascinated by the fact that he had sat near Hopalong Cassidy in a restaurant, or rather near the actor who represented him. (Hopalong Cassidy was a famous screen cowboy). I joined the Pony Club and had a tweed jacket, tie and Pony Club badge which I was very proud of. Theresa’s brother Dominic also belonged to the Pony Club, and much to the embarrassment of both of us our parents sometimes made us cycle together to a Pony Club ‘meet’. Sometimes the local hunt, which was nothing very grand, would have a special day when Pony Club members were welcome, and Dominic and I used to go. I loved hunting, although Dom relates a story about my pony lying down in some mud along a ride through some woods, and a burly farmer being able to pick up the pony, with me on top, and set it on its feet.

St Alban’s High School

My mother was very keen that I should to Wycombe Abbey, which was her old school. However, she had the theory that it didn’t do girls any good to board too early, so there was a three-year gap between Stormont, which finished at eleven, and the year she wanted me to start at Wycombe. For those three years I went to St Alban’s, partly I think because, believe it or not, a woman who had been my mother’s Scripture teacher at Wycombe was now teaching at St Alban’s. I was very unhappy there. The other girls had all been at the school from the start of their school careers, and had formed strong friendship groups, which I didn’t break into. I had a long and complicated journey to school which involved at least two buses, and once I was there, I couldn’t get home until the afternoon finished. On one occasion I was sick, and the school sent me home by bus. At each bus stop, it seemed, I had to get out of the bus to be sick and then get back on again. A further unhappy time was when my parents went on holiday to the south of France and arranged for me to board at the school while they were away. (my brothers were already at boarding prep school by then.) I hated it and was miserable. My mother went back to work around this time, and I used to have to let myself in to a large, cold and spooky house by myself after school and make my own tea. My mother had good reason to go back to work, but all the same I was very unhappy and alone because Granny had moved down to Studland by this time.

Granny

My grandmother was a big feature of my early life. She was a widow and had been since my grandfather, George Kewney, was killed when the Germans sank the ship on which he was Naval Chaplain at the battle of Jutland. This was the Battlecruiser HMS Queen Mary, which went down in 1916. Before the war started, George had taught navigation on board ship to Prince Albert, later George VI. My grandmother had a signed photo of Prince Albert, which had been given to George, and during my childhood the ink on the signature faded. Nothing loath, she sent it up to Buckingham Palace with a request that he re-ink his signature, which he did! Granny had had a very unhappy childhood. Her parents died of typhus in Edinburgh when she was quite young, and she was adopted by an uncle who didn’t really want her as he had two daughters already. He treated her unkindly, for example making her use the maids’ lavatory. When she left school, she was sent to a teachers’ training college to learn to teach PE. While she was there one of the other girls invited her to a Ball on board a battleship moored at Dartmouth. Granny wrote to ask her uncle for some money to buy a dress, but he refused, and said she should wear a petticoat which looked like an evening skirt, and the silk blouse she used to play sport in. Granny was not a wimp, and she went to the dance in the petticoat and blouse and met my grandfather. Legend has it that he danced twice with her on the quarterdeck, which was tantamount to a proposal in those days, pre first world war. My grandmother fell deeply in love with George and was supremely happy for a short time as his second wife. My mother was born in 1914, and so was only two when George was killed. One of the regrets of my life is that I didn’t comprehend the long-lasting grief that my grandmother lived with for the rest of her life; she never wore coloured clothes, as a sign of her mourning.

After George’s death Granny lived in a thatched cottage in South Brent in Devon, amazingly quite comfortably considering she didn’t work and had only George’s naval pension as far as I know. She brought my mother up thoughtfully, sending her to a co-educational school and then to Wycombe Abbey, and finally to the LSE where my mother took a diploma in social work. She then worked as a hospital almoner at St Thomas’s hospital during the war. So, after all this, my grandmother was deeply disappointed when my mother married my father, who was nearly twenty years older than she was. My grandmother was vindicated in this to an extent when my father died in 1958, leaving my mother to bring up three teenage children.

My grandmother lived with us at Mayfield, and then for some time at Moffats, but she never got on very well with my father, and when I was about eight, I think, she went to live in a private hotel in Studland in Dorset. She had a bedroom and sitting room and a roof garden, which was lovely. We children used to be sent to stay with her to convalesce from childhood illnesses. I did so after I had measles. Granny and I took the ‘Bournemouth Belle’ train from London to Bournemouth, then the small steam train from Bournemouth to Swanage, and then a taxi to Studland. We had lunch in the dining car on the express train, and I remember the soup slurping from one side of the plate to the other as the train swayed. Granny pointed out the primroses on the embankments on either side of the train as we steamed along, though you weren’t allowed to put your head out of the window in case you got smuts in your eyes from the coal in the engine.

Those visits started my life-long love of Dorset, and Studland in particular. Granny and I used to take the footpath from her hotel to the beach, and if it was a hot day, we pretended to be sausages sizzling in the frying pan. (not that Granny ever had to cook sausages as far as I know!) We used to visit Corfe Castle, and a special treat was crossing from Studland to Poole by the chain ferry, and on the way stopping to collect cowrie shells from the beach at Shell Bay. There were cowries in those days. We used to walk out to the Old Harry rocks, Granny pointing out the wildflowers as we went. I still love wildflowers. On the other side of the road from Granny’s hotel lived a friend of Granny’s who had a large garden, which we were free to use when we wanted. Granny used to take me there with my dolls and her sewing kit, and we would have a ‘make and mend day’, a naval tradition, mending my dolls’ clothes and making new ones. I hope she enjoyed those times as much as I did.

Back at Moffats, probably the most dramatic event of my childhood was the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth. I was eleven in 1953. Of course, it was deeply important for the whole country, but especially because it was a brilliantly bright moment when the country came out of the time of austerity and rationing after the war. My father was given two tickets for a stand on the coronation route by his club, and the question was, who in the family should have them? There was a family conflab round the dining room table. My father said that the three older adults had all already seen a coronation, either that of George V in 1911, or George VI in 1937. He said that the twins were too young to go, so that left Peter and me. It was decided that Peter would drive us up to London very early; people were allowed to park their cars in Hyde Park. Can you imagine that now? Peter insisted that we should have plenty to eat, so my mother made beef stew and mashed potatoes in two large thermos containers. When we ate lunch our neighbours on the stand could smell it all and were deeply jealous. We spent the day on the stand in, I think, Pall Mall, and we seemed to have stayed dry in spite of the drizzle, and we saw the Queen in her coronation coach, and the Queen of Tonga, who famously drove in the procession in her open carriage in the rain without putting up the cover, much to the delight of the crowds. During the ceremony the service was broadcast over loudspeakers so that the crowds could hear it.

While Peter and I were in London, the rest of the family watched the broadcast on the new television at the Vicarage, and then there were games for the children somewhere on a playing field. All the children were given coronation mugs, something else I wish I still had. The coronation marked the time when televisions began to reach many of the population, and our next-door neighbours had one. My father was deeply against tv, on the grounds that it would destroy family life (what would he think now?), so the twins and I used to sneak round to next door to watch children’s programmes. Muffin the Mule was a special favourite, and then later the same kind of historical serial as ‘After Sedgemoor’. My parents worried about losing us to the tv next door, and eventually weakened; my father claimed it was so he could watch Wimbledon.

Round about the same time Peter married Philippa, the daughter of the Vicar of North Mymms. I was a bridesmaid, and I think that marked a turning point in my growing up, as it was the first time I realised that I was actually quite pretty! The twins, as pages, wore red uniforms, some kind of mess dress as Peter was still in the Royal Engineers at that time. My father went to enormous trouble to see that the uniforms were authentic, and had exactly the right kind of buttons, belts etc. They must have been specially made, and they certainly looked spectacular. The wedding was exactly as weddings were then, service in church followed by a buffet meal, speeches, champagne and the bride changing out of her wedding dress and going away, throwing her bouquet to a bridesmaid (not me!).

When they were eight (and I was twelve) the twins went to boarding prep school at Forres in Swanage. There was quite a to do about getting them ready to go. First, they had to do some sort of test, but they did it at home and I think quite a bit of cheating went on. They were accepted, not much of a surprise as the school was run by some friends of my grandmother’s. Then they needed all the kit, tuck boxes, uniform etc. My mother paid someone to come and sew the name tapes onto all their clothes. I expect one of my parents took them the first time they went, but after that they took the school train. While they were at Forres, in May 1955, a tragic event took place. The boys used to spend quite a bit of time at weekends on Swanage beach, and on one occasion some boys, luckily not my brothers, were playing on the sand. One group of children threw some stones at what seemed to be an old piece of metal rubbish, but in fact it was a WWII bomb which had been swept up onto the sand by the tide. All five boys who were playing there were killed, and at least one was blown into such small pieces that no trace of him could be found. There was a long article about the boys’ deaths in The Times, with a sad picture of one of the fathers scouring the beach for some sort of trace of his son. The school held a memorial service and put up a board in the school chapel; sadly, the school has now closed, though it has re-opened as a school for autistic children. The memorial to the five boys who died has inscribed ‘Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God’.

During my childhood almost all of our fortnights of summer holiday were taken at Sheringham in Norfolk. My father’s brother and sister both lived in Sheringham, his sister in a house on the cliff which had been the family’s holiday house. Some years we stayed with Auntie Queenie above the cliffs, and other years in a boarding house in the town. I loved Auntie Queenie, and she and I had a great deal in common. She had plenty of books, mainly history and romances, which I used to borrow and relish. She also had a regular reservation of two seats in the back row of the Sheringham cinema, and she used to take me with her, usually for blockbuster adventure stories. Sheringham has quite high tides: a sandy beach which is topped by a section of huge pebbles. When the tide is in the beach is not very enjoyable. We used to spend low tide on the beach, picnicking, making sandcastles, swimming and searching the rock pools. During high tide we went in land, to a place called Pretty Corner. This was acres of rough land with birch trees and bracken. Bundle the dog came with us and we played hide and seek, made dens and climbed on fallen trees. Lunch always seemed to be jam sandwiches and our hands would be covered in wasps. We children loved Sheringham. My uncle Leslie ran the lifeboat station, and it was a challenge to swim from Auntie Queenie’s house along parallel with the beach as far as the lifeboat station, which seemed a long way. One year it rained just about every day for two weeks. Peter was with us on that occasion, and he and my father made a large battleship out of cardboard. It was supposed to entertain us children, but Peter and my father became so engrossed, and the battleship became so important, that we were not allowed to touch it.

My mother hated Sheringham and longed to go somewhere warmer and more glamorous. Finally, she got her way, and one year, when I was about fifteen, we went to the Isle of Mull, though this was neither warmer nor more glamorous! Getting there was going to be a problem. We acquired a trailer which could be towed behind the car, and I was deployed to make a canvass hood so that it could be used as a sort of tent. I was seriously into sewing and dress making at that time. We also had a tent, so Nigel, and my parents were going to sleep in the tent, and David and I in the trailer. In those days before motorways we would need two nights on the way. The first night we spent with my godfather in Yorkshire, which was very comfortable. The next night we camped by Loch Lomond, which should have been romantic and beautiful, but was in fact ruined by a storm. We reached Oban, where we had arranged to leave the trailer, and got the ferry to Tobermory, and finally drove to the bothy we had rented from a friend of my mother’s. This turned out to be extremely primitive, with no electricity or running water, and its only heating a wood fire, for which we had to scour the surroundings for wood and kindling. The water had to be pumped up by a hand pump, and we had to take turns in manning the pump. My father, who was born in 1896, came into his own because he remembered how to trim oil lamps, and how to make fire lighters out of newspaper.

You might have thought this holiday would have been a failure, but not so! We were on Mull in early September, and this turned out to be the most popular time of year for parties on the island. Because of my mother’s contacts there, we were asked to endless dances and parties, in large houses and even in a castle. All the dances turned out to be Scottish reeling, which luckily I knew quite well as we were taught it at Wycombe. My father managed to ring up our cleaner at home at Moffats, and ask her to post his dinner jacket, which amazingly she did.

We were sorry to start for home. When we reached the quay side we were told that the weather was too rough for the ferry to berth, and we would have to go to the next port down the coast and catch a cargo vessel, which happened to be full of cows. Our car was winched onto the boat and into the hold, among the cows. My mother was told she could use the vessel’s galley to cook us the bacon and eggs we were to have had while camping that night, and I remember the enormous frying pan she had to use. The weather was so horrific it was decided to drive home through the night rather than camp, which we did, so the canvass trailer cover, which I had struggled to design and make, was only used once.

Wycombe Abbey

In 1955 I finally left St Alban’s and went to Wycombe. My parents hoped that I would get a scholarship, as money was tight, and before I went, I sat the scholarship papers over two or three days in a bitterly cold winter. There was never much hope that I would get an academic scholarship, but I enjoyed sitting the exams because I took them in the home of one of the St Alban’s teachers, which was lovely and warm, and I was given hot drinks and biscuits during any breaks. Later my mother took me to Wycombe to be assessed for a Seniors’ scholarship, which, if you passed the interview, gave you a reduction in the fees if your mother or another relative was a Wycombe old girl. This time I did succeed, largely, I believe, because when asked what I was currently reading I said ‘The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’, which, as it happened, was true. ‘A book of verses underneath the bough…’ My mother, throughout my childhood, told me endless stories about Wycombe, and she did make several lifelong friends there. She showed me idyllic photos of her own time at school. During the summer term before I went, she took me to the school to see ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, and with all this preparation I was scarcely homesick at all.

Academically I didn’t get off to a very good start, being called a ‘mathematical idiot’ by the Head of Maths. However, I did enjoy the whole boarding experience. I made one very good friend, Sue Agnew, with whom I’m still in touch, as I am with Dellie Gray-Fisk and Janet Ashton. Wycombe was quite a tough experience, much, much tougher than it is today. Winters were colder then, and because I was in Cloister House, which is quite a walk from the main school building up a steep hill, Sue and I were often tramping up the footpath in the snow or rain. The main winter sport was lacrosse, and we were made to play for half an hour before breakfast, and in the afternoons too, and however cold the wind we were not allowed a woolly hat, so my ears were permanently in agony. On one occasion the main path up to the House was being re-tarmaced, and we had to take a long way round. It was freezing and snowing. When we finally got up to the boarding house and went into the dining room for supper, it turned out to be shepherds pie, nice and hot. Just as we were about to start eating, someone from the kitchen came in and shouted ‘stop eating girls, stop eating! The shepherds pie is bad!’ No one took any notice, and we gobbled up our supper. Later the House Mistress asked why we had carried on eating. ‘Either it will make us ill, in which case we could have a couple of days off school, or it’s fine, in which case we will have had a hot supper. The alternative meal was spam. Ugh!’

Wycombe is a very Christian foundation. We went to chapel every morning, and twice on Sundays. In the evening we had prayers in the boarding house, and whoever was the ‘house musician’ had to play the hymn. Sue was house musician, and her repertoire was very limited, though not as bad as my mother’s house musician, who could only play ‘Through the night of doubt and sorrow, onward goes the pilgrim band….’ Not very cheerful. Towards the end of my career I joined the chapel choir, though I’m not a very good singer.

Our lives at Wycombe were very regimented. Girls were divided into Houses, and I was in Cloister, which was my mother’s old house. The day was rigidly divided into lessons, prep and games, and we had very little free time, especially in the younger years. 1955 was less than ten years after the end of the war, and only a year after the end of rationing. Our food was very basic. We had our main meal at lunch time, and it was quite often ‘heart’ – I don’t know heart from which animal. Breakfast was cereal, and sometimes tinned tomatoes on toast. Sunday breakfast was white rolls, just as the grandmother had in ‘Heidi’, and we looked forward to those and to trifle for Sunday lunchtime pudding. At tea we had bread and butter, and you were allowed to bring your own jam, if I remember correctly three pots. When you opened a new pot of jam you used to ‘christen’ it, usually after a boyfriend or a pop singer. Most of the girls in the house lived in the ‘House Study’ in any free time or while doing prep. In the Cloister house study we had, amazingly, an open fire, which was allowed on Sunday afternoons, and we used to toast marshmallows on it. Today the authorities would have had kittens about health and safely. If you were made a prefect, or ‘Mon’, short I suppose for Monitor, you lived in the Mons’ Room, which was much smaller and quite cosy. In the house study there was a wind-up gramophone which took metal needles, and we used to play 78 rpm records endlessly. Of course there was no television or computers, and I don’t even remember a radio. We slept in dormitories, actually not as huge as my brothers’ at Rugby – the largest had only eleven beds. For the first week or two of term we all had our temperatures taken every morning when we got up to make sure we had no infectious disease, as there was no MMR then, and anyone could have had whooping cough, measles, scarlet fever etc. Sue used to faint on several mornings, as it was before breakfast. As you got older the dormitories got smaller, and towards the end of our career Sue and I shared a two bed dormitory, which had a loose floorboard and we took delight in hiding sweets under the floor. What a simple pleasure.

One interesting fact about Wycombe Abbey was that during the war the school buildings were requisitioned by the War Office, and the girls were evacuated to various other schools for the duration. The buildings and the grounds were taken over by the American Eighth Air Force Bomber Command. The school buildings and most of the land were handed back in 1946 when the war ended. While I was at the school, however, the American air force still occupied a big area of the grounds, because of the Cold War, and while the Wycombe site is very hilly and the land folds such that you can’t see one part from another, with care we could find a spot on the fence from which you could admire the GIs in their neat uniforms. On the wall in the main school entrance hall is a plaque with the words: ‘In these buildings were conceived, planned and directed the mighty air assaults on Germany which, with those of the Royal Air Force, paved the way for allied victory in Europe.’ Sadly there is another war time connection – Glenn Millar played his last concert on the terrace at Wycombe on 29th July 1944 before his plane disappeared over the channel on his way to France to organise a Christmas concert for the troops in liberated Paris. No one knows how or why his plane vanished.

Finally, I reached the end of my school career. I stayed on an extra term in the UVI to take university entrance exams to Oxford, Cambridge and London universities. By the end of three weeks of exams I was exhausted. I was offered interviews at both Oxford and Cambridge and went off by train to take them. At Cambridge, Dom was already a student there and as I had to stay the night, he came to take me out, bringing a present of a bag of oranges! I had been made to go to the interviews in my school uniform, and the reason came clear when one of the Cambridge Dons said, ‘ah, we haven’t had anyone from Wycombe for a few years’, and sure enough, I was offered a place. I remember my house mistress telling me in the evening on almost the last day of that term, that the Headmistress had a telegram for me. I was not allowed to go down to see her in a cardigan, in spite of the cold, as she hated cardigans! But it was an offer from Cambridge.

My father’s death.

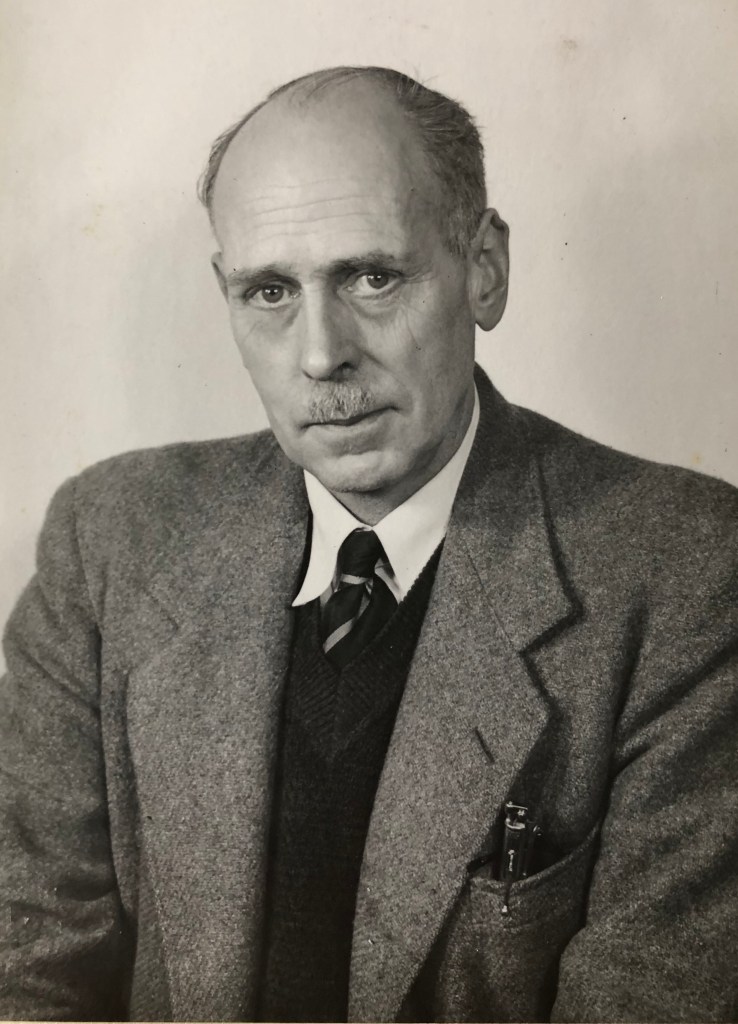

The holiday on the Isle of Mull turned out to be the prelude to my father’s death. In 1951 the rifle he had designed while working at Enfield had been chosen as the standard rifle for the British Army, but with a change of government the decision was reversed. A Belgian rifle was chosen for political reasons to take the place of my father’s gun and he was asked to bring the Belgian rifle up to the required standard. All of this had a profound effect on my father. He left the Civil Service in 1956. He then had short periods working for two engineering companies, until his death in 1958. Some time previously my mother had gone back to work at St Thomas’s hospital as an almoner, and because of her job, which brought her into contact with tuberculosis patients, my mother and her husband were selected by the hospital to have chest x-rays, and my father’s showed a patch of cancer on his lung, probably caused by heavy smoking and also possibly the trench fever he contracted during WWI. He had a lung removed, and in the custom of the time, he was told that he had had TB. I don’t know whether he believed this lie or not. The surgeon told my mother that the cancer had been caught so early, that if there was any justice in this world, my father would live. Unfortunately, the cancer spread over the next year or so, and reached his brain, which was found when he fell off a ladder in the garden.

1958 was the year that I took O levels. Sometime during that year my mother came to Wycombe during one afternoon to tell the headmistress that my father was going to die. In those days all news of that sort, and any experience of death, was kept, as far as possible, from children. My housemistress told me, and a friend, Mary Davies, that she wanted us to spend some time in the craft room designing a costume for Mary to wear as Perdita in ‘A Winter’s Tale’ which the school was putting on. We spent the afternoon on this, and I felt unpleasantly deceived when I discovered the truth later. Similarly, while my father was actually dying in hospital, my brothers and I were sent away to stay with various relatives, and we didn’t come home until the funeral. So, we never had the chance to say goodbye, which I think was a cruel mistake.

On the morning of the funeral I was told to stand in the hall at Moffats and to open the door to visitors, accept any wreaths or flowers and make a list of the donors. My father was well known in the parish and there were many flowers, and the smell of lilies, in particular, still takes me back to the trauma of that time. It was if anything more traumatic for my brothers, who were still at prep school; it had a profound effect on all of us.

The funeral took place at North Mymms Parish Church. My brother Peter’s father in law Lionel Hamel-Smith was the vicar there and took the service, of which I have powerful memories. My father was cremated, as was my mother, and they both have a grave at North Mymms.

When my father’s affairs were wound up it was found that there was very little money left. My mother wanted to sell Moffats, which was quite unsuitable for a woman alone, but this took some time. Finally, it was bought by a builder who thought he could get planning permission to build on the field which my parents had bought with the house in 1946. (He never was able to build on the field). I found out some time later that my grandmother paid for the cottage in Essendon which we moved into from Moffats. Peter was hugely helpful over the whole move. My mother sold many of the good pieces of furniture from the house, and also my father’s collection of antique guns, many of which would be worth money now, but it was an emergency, and we did finally move to the cosy and attractive cottage in which my mother spent most of the rest of her life.

Both my brothers and I had astonishing strokes of luck in the immediate aftermath of my father’s death. One of the twins’ godparents unbelievably generously offered to pay the school fees of both of them at Rugby, where they went to public school. At the same time Hertfordshire County Council agreed to pay my school fees for the remaining two years of my sixth form at Wycombe, on the grounds that I would get into university.

Cambridge

I left school at Christmas of 1960 and was due to go up to Cambridge in the October of 1961. That left several months empty, and my mother was determined that I should earn some money in the interim. I had had various holiday jobs previously: I had worked at the local hospital in the pharmacy and in the occupational health department. I enjoyed occupational health, as it mainly involved helping long stay patients, mainly men, to make toys for their grandchildren. I have stuffed quite a few teddy-bear tails. I also worked for a few weeks at the laundry in Potters Bar. The owner spent time with me showing me how the laundry worked, and teaching me to iron shirts etc. I quite often think of him when I am ironing! The women who worked in the laundry loved to wash and iron the hankies of Aker Bilk, a very popular clarinettist and singer of the time, whose record of ‘Stranger on the Shore’ was the biggest selling single of 1962. We knew whose hankies they were, as Aker Bilk had a bowler hat and a clarinet embroidered on his clothes.

None of these jobs were going to keep me employed for nine months. After I had unsuccessfully looked around locally, my mother – and I still can’t decide what I think of this – more or less forcibly put me on the Green Line bus and told me that I was to go up to London and look for work there. I spent the first few nights staying with a school friend who lived in London, and scoured the papers looking for a job I could do. The only possibility seemed to be filing – no computers in those days. I applied for a job filing in a hire purchase company. At the interview I naively answered all the questions about my schooling, and the interviewer decided I was too good for filing (!) and put me at a desk answering the telephone and giving settlement figures to clients wanting to sell their cars early. This involved doing percentages rather quickly, which readers will know is not my strong suit. I managed. Each hire purchase agreement was recorded on a punch card, and when a payment came in each month the card was taken out of a filing cabinet and moved into a different room, where employees at large punch machines entered the payment and recorded the new balance on the account. It was not a reliable system, and often mistakes were made. When they were, I and the other people in my office would try to rectify them, but if we failed, we used to put the punch cards in our bags, take them home secretly and destroy them. I often think of all the lucky customers whose debts were mysteriously written off in this way.

During these few months I was lucky enough to stay in a house in Sloane Avenue. It belonged to the sister of one of my mother’s neighbours in Essendon, and she lived there pn her own. I rented a room for next to nothing, plus breakfast, and if I remember rightly, quite often dinner as well. I think she enjoyed the company, and also the fun of seeing my boyfriends come and go. I was paid, I think, £8 a week, which paid my rent, my bus fare and my lunches, and left change to buy clothes and so on. I had lunch in a café just round the corner from the office, and for three shillings you could have a main course, like roast pork with trimmings, and apple pie. This was the ‘swinging sixties’ and the time of mini-skirts, bistros, parties and general fun, a good time to be in London and I enjoyed it. Working in London certainly opened my eyes to the world.

So, in the October of 1961 I finally went up to Cambridge, and it didn’t take long to realise how rarefied the atmosphere was, how hard you were expected to work, and how intelligent the other students were. My supervisor was Professor Muriel Bradbrook. She was deputy Mistress of Girton at the time, and a famous Shakespeare and Ibsen scholar. She was terrifying. My first supervision, together with three or four other girls, (Girton was all female) was typical both of us and of her. She handed out a poem on a sheet and asked us to comment. None of us knew the first thing about it, but it turned out to be the Shakespeare sonnet ‘Like as the waves make towards the pebbl’d shore…’ This was rather humiliating. There were other famous names lecturing in English at Cambridge at that time: C.S. Lewis for one. He must already have been ill with the kidney disease which killed him in 1963, and perhaps that was why he lectured in Medieval literature in a beautiful panelled hall in his college, Magdalene, rather than in the clinical lecture rooms in the faculty buildings in the main town. F.R. Leavis also lectured at the same time, about ‘the great tradition’, which comprised Austen, George Eliot, Henry James, Conrad and DH Lawrence. He believed in the profound human value of some of literature. He had a considerable following and was as popular in his own way as any pop star, but I found him intimidating and rather dry. This is a criticism of me rather than of him.

My first year at Cambridge was also Dom’s last. We had many meals out together, at the Indian restaurant opposite St John’s and at the Gardenia, which still exists. The Gardenia was famous for serving spaghetti and chips, shepherd’s pie and chips, pizza and chips, risotto and chips….. You get the picture.

Reluctantly, Dom took me to my first May Ball. Not long after that he left for his first posting with the Army, and although we corresponded very regularly, I didn’t see him again for a long time.

I was used to being driven up to Cambridge by Dom during my first year, so it came as rather a shock when I had to travel up by train at the beginning of my second year. I had a great deal of luggage and a friend and I were struggling to get to Girton from the station – which is at the exact opposite end of the town – when an army land rover with a trailer towing a machine gun stopped and offered us a lift. We piled our luggage in, and I tied my eiderdown to the gun barrel. In this way began my friendship with Philip Vignoles (and his wife Lucy) which continued until their deaths. Philip was an undergraduate but belonged to the University army cadet corps, which allowed him quite a few privileges, including having a car at Cambridge, which was a serious exception.

I could have made better use of the academic side of my time at Cambridge than I did. In the 1960s the English syllabus was huge and covered just about every period of literature. It started with ‘Gawaine and the Green Knight’ and finished more or less with T.S. Eliot. It seemed that every week students would be asked to cover another giant of the cannon. For example, I can remember, or at least I think I can, being asked to read Dickens and write an essay on his novels in a week. The result was reading at great speed and not in much detail, and then relying on books of criticism far more than was desirable. There were of course students for whom this was the perfect challenge, but I was not one of them. The final outcome was a degree which furnished you with a broad knowledge of much of literature, but not as much depth as perhaps it should have. I feel worried about criticising a world class institution like Cambridge, but I have over the years heard others say the same things. However, the course did mean that as a teacher, whatever books the exam boards chose to put on the syllabus, the chances are that someone who has been through the course should have at least a working knowledge of them. What should I have done, with hindsight? Work harder, change subject? When I left school I had little or no idea what else might have been possible. I had a wonderful three years in a beautiful place with great friends, and a Cambridge degree on my CV kept me in employment for my whole working life. Maybe that’s enough.

.

Jo Spearman has forwarded your posts. My Name is Karen Drake.. Through lockdown I have been studying all the children of Edward Pembroke’s children, one of whom was Helen Mary. I am Queenie’s grand-daughter. I am Patricia Vinnicombe’s daughter.. I was interested to read Gill’s history.

I remember The Drift in Sheringham as I lived there for part of the war., and stayed there often and in later years with my children.

I am interested in memories that Gill may have of the family

LikeLiked by 1 person