Tom Memoirs Chapter 11, Darwen up till 1947, continuation of continued

… I do remember the one and only good hiding I got from my mother very well. It must have been around 1944, so I’d have been 7 (I was eight in the September, and it was in the summer). At that time there was double summer time, to give the farmers more daylight in the evenings. Which meant that it didn’t get dark till around 11 pm or even after. We’d been playing in the woods (Sunnyhurst Wood, that is). The woods backed onto the houses across the road from where we lived. We’d gone into the woods, as we often did by going through the garden of Peter and Michael Fish. The Fish family lived just across the road from us and a bit to the right (downhill). Their house was called Rokeby, presumably after Walter Scott’s poem. The family at the time consisted of the dad, Shepherd, (Shep) Fish, headmaster of one of Darwen’s secondary modern schools, his wife, Alice I think, and the two boys, Peter about four years older than me and Michael, two years older than me. (Lots more about the Fish family to come; a big forming influence on me).

It must have been – I’ve no idea – maybe eight in the evening and we all began to make our way home. Peter had gone in and then he came out again because he’d left his jersey on a bench in the woods not far away. He’d just started that year (I suppose) at Bolton School, where boys went if their parents decided that Darwen Grammar School was not good enough, and they could afford it. It was fee paying, like MGS I imagine. It was quite a commute too from Sunnyhurst to Bolton School, a bus, a train, then another bus, I think. Anyway, when he got to the park bench, the jersey had gone and everyone was muttering that now Peter really would be for it – in big trouble. It was part of his school uniform, a grey V-neck jersey with stripes in the school colours, black and white round the V-neck. So Peter went in to face the music, every one else went home and there was just one kid, Brian Holt and me left, also about to go home. Brian was about two years older than me, and Michael Fish and Brian were best friends. Brian reckoned that he had just noticed a man in army uniform pass by and he thought that he may have taken Peter’s jersey. So we decided to see if we could find where he’d gone and hopefully get the jersey back. At least Brian decided this, and I just went along. So there we were, Brian going somewhere purposefully, with me just following . There was no discussion of where we were going or why. And like that we went up to the top of the woods and then up to the lower (I’m almost sure) of the two Sunnyhurst reservoirs, and there was this soldier, by the bank of the reservoir, fishing, fly fishing for trout I later found out. Brian went up to him and I stayed at a good safe distance because of my fish phobia. And then I waited and waited and waited. Brian was getting on very well with the soldier. When it started to show signs of going dark, I thought I’d better go home, which I did. When I got home, my grandmother was very relieved to see me and also very angry because it was so late and they’d been very worried about me. My mother was not there, she had gone to the woods looking for me. So then I went back to the woods, as ever through the Fish’s garden, and quite soon, I’m glad to say, I found me mother wandering about, looking for me, calling “Tommy” (I don’t think I’m making that up.) So then we walked home in total silence, and when we got home, I got a very good telling off and then my mother put me over her knee and hit me on the bottom with her hand as hard as she could, numerous times. I cried as was expected, though I don’t think the beating was very painful; then I was put to bed. The whole incident was witnessed my my mother’s cousin, Annie (Yates, formerly Sgalitzer) who was staying with us on a visit. I later found out that the soldier had indeed taken Peter’s jersey, a bit of simple thieving I suppose, but he gave it to Brian who returned it to Peter in due course. End of story.

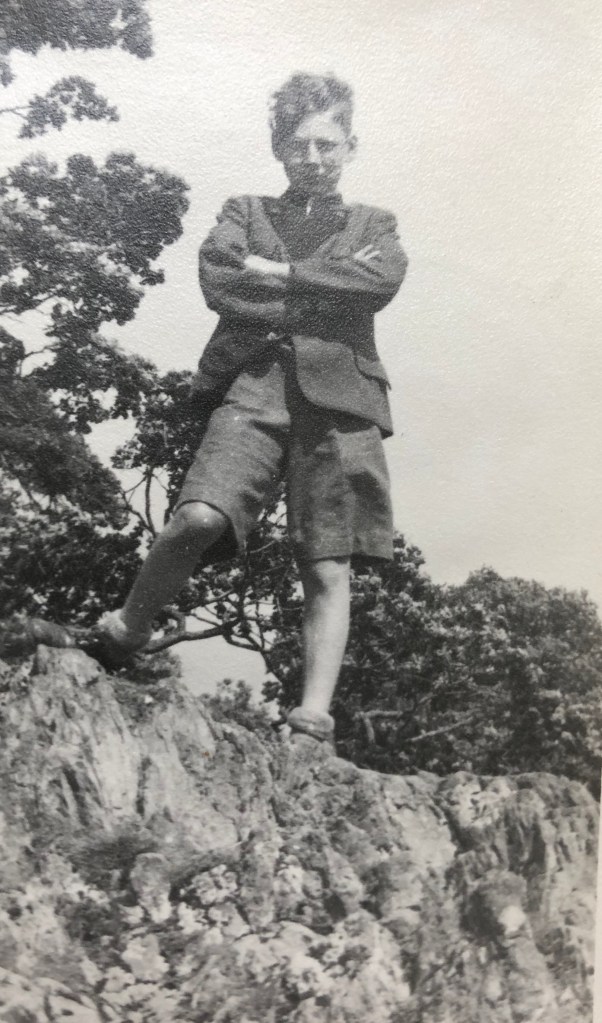

Now I’d better tell you about the Fish brothers, Peter and Michael. Until he was maybe thirteen or fourteen, Peter was the undisputed leader of our gang. (Then he got into adolescent interests.) Around our part of Sunnyhurst there were perhaps a dozen, maybe fifteen, boys from a year or two older than me to a year or two younger. There was no one within a year of my age. There was a very fierce rivalry between Peter and Michael, and Michael regularly formed rival breakaway gangs, which always consisted of Michael, Brian Holt and me. (I think that could have been the origin of a rebellious streak in my nature).

There were a few girls around, one saw them at school a bit, though very little actually. I think some of them went to private schools. Anyway, girls never came out to play. They must have visited one another and played indoors, but anything I say will be guesswork. Outside of school, it was a 100% boys’ world.

Peter was the oldest in the gang by at least a year and he was a natural leader; he was pretty wild, a real dare-devil, a brilliant, yes brilliant, climber of trees. Both he and Michael picked up a lots of information from their father; I remember Peter getting us all to play American football which was completely unknown in Darwen (as was rugby); he must have learnt about it from his dad. He also often had playing war games, for example having us all sitting in different positions in a tree, and we were a bomber crew over Germany; taking off, finding our way to the target, being shot at by Messerschmit 109s and shooting back, being shot at by anti-aircraft guns on the ground, dropping our bombs, or being shot down; if not shot down, limping back to England, full of shell holes and with only one engine working; if shot down, parachuting into Germany and working our way back home. (We never got killed). I was always the bomb aimer, because that was the lowest position in the tree and so the easiest to get to. (I was the worst tree-climber). We played endless variations of war games like that; commando raids, etc. Plenty of sneaking up behind German guards, putting one hand over their mouth to keep then quite while cutting their throats with the knife we had in the other hand. Hi-jacking German army motor bikes and going on raids on them…

Peter in particular was very good at tying ropes high up on trees, which we could swing on; (where did he get all those ropes from?) In one place, there was a row of smallish trees, and Peter would set up a succession of ropes so that it was possible, even for me, to swing from tree to tree just like Tarzan in the Tarzan films (always acted by Johnny Weissmuller at that time). We called them the Tarzan trees. Again the Fish brothers were well informed about the Tarzan books, Edgar Rice Burroughs, what the “real” Tarzan was like, how the Hollywood films got it wrong, … This must all have come from their dad. Once Roy Holt, the younger brother of Brian Holt, who was about a year younger than me, let go of the rope he was swinging on and fell from a pretty great height; the tree to which the rope was fixed was at the top of a steep slope, and he let go at the far end of the swing. Very fortunately, he had a soft landing on a thick pile of dead leaves and was completely unhurt.

Peter also, for example, organised us into playing at wild western train wreckers; there was a long bank very suitable for that near the Sunnyhurst Tennis Club. The game was to jump onto the back of the train, climb onto the roof, make our way to the engine at the front, overpower the driver and fireman (coal shoveller), invariably by slugging them on the head with a huge spanner; then stopping the train, robbing the rich, greedy passengers and galloping off on our horses that had been trotting along behind the train.

Another thing that Peter was very good at, better that any of the rest of us, was making up kits of wartime aeroplanes. You could buy these kits (for solid, not flying models) which consisted of partly finished sections of the aircraft made from balsa-wood, which you could finish with a good knife or a razor blade, following the plan that was supplied, glue them together with “balsa cement”, transparent glue in a tube, add the wheels, propellers, etc., plus RAF or Luftwaffe or whatever insignia (also American, Japanese, etc.) and then painting them. (Actually adding the insignia after painting them of course). Peter made lots of these and made a display of them flying around, suspended on cotton threads, in the front porch of his house. It really looked fantastic, to me at least. (Everyone used the back door, so no one ever went through the front porch). And he was also the best of us at making up kits of working (really flying) balsa-wood planes, a balsa-wood skeleton covered in tissue paper and painted, driven by a propeller which you wound up with an elastic band that was inside the fuselage (running from a fixing point at the back end of the fuselage to the propeller).

My mother once made me a model aeroplane, just a cardboard cut-out, nothing fancy like balsa-wood, but it was quite a complex business – it was a real model in three dimensions, and needed a lot of careful cutting out and glueing, but my mum was good at that and enjoyed doing it. She made a Catalina flying boat, and I was very pleased with it, and had it hanging from the lampshade in my bedroom for quite a while. Years before (when you’re seven, two years ago is “years before”) she put together a kit for a model windmill for me. You could pour sand – supplied with the model – down a chute and it made the sails turn, something like that, another vague memory. But I thought it was great. But I remember very well looking for it one day and it had disappeared. This is something that happened from time to time. Mothers have a way of chucking out or giving away old toys – and books – without consulting the owner; very vexing!

Now to Michael Fish. Outside of school, I played with him more than with anyone else up to 1947 and he influenced me a lot; actually, when I think about it now, it was often Mr Fish who influenced Michael, who then passed things on the me. In fact the Fish family emigrated to Samoa, presumably British Samoa, in the South Pacific soon after the war, in 1948 if not 1947; (there was a third child, a boy called Nigel, born at about the same time as Jimmy, so the family that emigrated was Mr and Mrs Fish and the three boys). Mr Fish must have got a job there as a headmaster, but I never knew just what happened. Anyway, it was a great adventure for the family, to leave austere, damp old England just after the war, and to move to one of the remotest corners of the world.

I never really chose Michael as a friend, he was two years ahead of me at school and about two years older than me; in fact his best friend was always Brian Holt who was the same year as he was. I guess he must have chosen me. Many of my memories are of playing with him indoors when the weather was cold/wet or it was dark. My family never objected to my having other kids in to play. When I think about this now, it was really exceptional. I was never invited into the Fish house, or the house of any of the other kids up Sunnyhurst, apart from birthday or Christmas parties. And in fact there were very few parents who regularly organised parties for their kids. More later.

I hardly ever set foot in the Fish house, sometimes just to step inside the door while Michael was getting ready. The odd thing about the houses across the road from us was that their fronts faced the woods and their backs the road. Hence Peter could fill the front porch with a display of model aeroplanes criss-crossing it; no one ever used the front door. Maybe the houses were build before the road (in the 1920s or 30s) and the road was build afterwards behind them. Very odd. So when you went to the Fish house you arrived from the road and came to the back door and then into the kitchen. This was a big living room/kitchen, with a coal fire burning and Mrs Fish always seemed to be sitting by the fire smoking a cigarette. She always ignored me. I remember once calling for Michael in the morning and he was in the middle of eating a bowl of bread and milk; just cut up bits of white bread with milk and sugar, as it you were having cornflakes; (I didn’t know that corn flakes existed at the time). Soon after, I tried it at home out of curiosity; it wasn’t very good; I don’t recommend it. Were they so hard up?

Michael, no doubt through his father, was very enthusiastic about King Arthur, all the Round Table stories, knightly honour and chivalry, great courtesy and concern for women. We played endless games based on this both, outdoors and indoors. Indoors I remember that we build castles with my child’s building bricks, or sometimes even with the furniture in my bedroom, even once or twice in the sitting room. We made plasticine models of ourselves as knights, of our horses, our beautiful ladies, our enemies, and staged very chivalrous fights and battles. We were always very good, honourable, … the villains quite the contrary. Brian Holt sometimes joined us, and we swore ourselves to secrecy, because we felt other kids might laugh at us. We called it our secret game. At one time we each chose a glamorous film star to be our lady partners. Michael chose Rita Hayworth, Brian chose Susan Hayward, and I was allocated an English actress, Sally Grey, because I couldn’t name a single female film star at the time (I was maybe 7 or 8).

On one occasion, when I was playing with Tony Collins with whom I also played a lot – more below – I told him about our secret game and swore him to secrecy. He then told Michael straight away that he knew about our secret game and Michael was really mad at me and really knocked me about and I had to swear I would never mention it to anyone again. In the event I don’t think anyone else was interested and no one laughed at us. We also played endless other games, Robin Hood and co.; with home made bows and arrows which my grandmother, especially found very hazardous; and Beau Geste games, as soldiers in the French Foreign Legion fighting in the Sahara, and 1920s gangsters with Tommy guns, blazing away in our get-away cars, and pirates, and coastguards, and Flash Gordon travelling in space, and the Scarlet Pimpernel, rescuing French aristocrats from the guillotine; we got a lot of our ideas from the Saturday matinee films we saw. Believe me, I’m not inventing this.

The thing is that all that thinking and talking about extreme chivalry, honour, virtue, stuck with me as I grew up; a very romantic, immature, idealistic idea of true love, of perfect love that was forever, at that time massively reinforced by Hollywood films; I guess I wasn’t the only one. No one ever told me anything different, and as I was at an all-boys boarding school and never saw any girls in the holidays, … I don’t know what to say – but it wasn’t very two-feet-on-the-ground.

Indoors we also played lots of board games, from ludo and snakes and ladders to draughts and chess to monopoly… In fact we had an Austrian game called Trust, almost identical to Monopoly, all in German of course, so everyone had to rely on me to read the Chance (Zufall) and Community Chest (Amtskasse) cards, till they got to recognising them. The properties, instead of being London streets were town inthe Austrian provinces. This meant that in each set there was one more expensive place, a medium place and a cheaper one; the green set for example was Graz, Leoben and Hartberg (I can remember them all). Also you couldn’t mortgage properties, but we did anyway, just as in Monopoly. And the tokens were like little skittles in different colours, not a patch on Monopoly where there was the top-hat, the car, etc.

At one time we were fascinated by divers, 1930s style. You saw adventure films, there were stories in comics with divers. Connected to a ship or boat by a rope, breathing through an air tube that ran up to the surface, communicating with the surface by a code using tugs on the rope. Three long tugs meant an extreme emergency; pull on the rope as hard as possible, if necessary until it breaks. There were lead weights in their boots and they wore huge spherical brass helmets. They were always getting into fights with villains, being attacked by giant squids, trapped in the grip of giant clams. So we played at divers; both outdoors, and also indoors using plasticine models of divers that we made.

When the weather was good or at least not bad, we roamed the moors, the countryside, for miles and miles. There were several disused quarries where we played; again I was very timid and careful and was often watching while the others were doing all sorts of climbs up the quarry walls.

We often went to a village called Tockholes where there was a stream called Rocky Brook, (very popular for family picnics on summer weekends), where we (everyone except me) would fish for minnows and sticklebacks, using jam jars with the opening covered except for a small hole; the minnows and sticklebacks were very obliging and easy to trap. I went along because I wanted to be with the gang, but I always dreaded coming anywhere near a fish, living or dead. Again, the other kids were either very understanding and considerate, or so self absorbed that they were not aware of my terror of fish. Either way, I had no problems. These and other outings were often picnics, and we would go off with the picnics that our mothers had made and eat everything we’d been given about ten minutes later.

We really went all over the place, really roaming for miles and miles. In the woods, on the moors, often crossing fields where there were horses, cattle, sheep, sometimes really scared that there may be a bull that would attack us, or that the horses that towered over us would turn nasty. Almost always I was the youngest; there were quite a lot of kids around younger than me but they somehow were kept in by their parents much more. So this mean that in all this wandering around, it was always someone else who knew what we were doing, where we were going, and once we were out of the range of where I knew where I was, I just followed the others. And I must say, I was never left behind.

We sometimes went to a ruined house miles, let’s say a mile, from nowhere, known as Old Aggie’s. It was all boarded up and crumbling, but we used to manage to run around on the roof. We’d all heard the story that Old Aggie lived there by herself many years ago, and at weekends, she served teas to walkers. And one day she was murdered by thieves who had come to steal her money. A good bit further on there were the remains of another house known as Lyon’s den, because a man called Lyon had lived there. Then there was Hollinshead Hall, also just the remains of foundations and an outbuilding which we called the dungeon. This was never locked and we used to play there sometimes; not all that often as it was a good way away. As well as the two Sunnyhurst reservoirs, there was one, also some miles away, called Red Leigh where we went two or three times.

The last time that I went to Hollinshead Hall, it was with just Brian Holt, soon after the Fish family had moved to Samoa. We had our picnic, or what was left of it, in the dungeon. Brian had a tin of condensed milk, and he made a huge mess on the walls of the dungeon pouring and spreading condensed milk all over the place. Nothing was said. Brian must just have had the urge to really make the most horrible mess he could of a nice place. I was bewildered and amazed.

From Old Aggie’s you could see a wood called Step Back across a small valley. It was said that during the civil war, some of Cromwell’s men had stepped back into the wood to avoid being seen by royalists. And then there was the explanation that Step Back was a garbled form of Steep Beck.

And of course, there was Darwen Tower. Built on a high point on Darwen moors overlooking Darwen to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. Just about 1000 feet above sea level, about a mile from our house, you could walk up in 20 to 25 minutes if you were fit; it was quite a steep walk. Michael Fish always insisted that it was exactly one mile from his house.You can read all about it via Google, how tall, how much it cost, who paid for it, and see lots of photographs ancient and modern.

We went there occasionally, but it was kept locked during the war, so that the Germans wouldn’t be able to parachute soldiers in to occupy it or ??? It was not really very exciting. A tower with a spiral staircase, all in stone except the last bit of the stairs which were metal. There were two levels with a viewing terrace, a bit less than half way up, and at the top. The views were great. It was said that on a very clear day you could see the Welsh mountains, Blackpool Tower, the sea, … but there weren’t so many very clear days. Still there was a great view of our house, Darwen, parts of Blackburn, the moors, … I remember once seeing a faint, ghostly outline of Blackpool Tower.

When I was small, it had a green glass dome. This was blown away in a storm, I think when I was still at primary school. That was quite a drama. The tower was then domeless for decades, and it you read up its history on the internet, it was really neglected for ages, but later, in the 1990s?, it was done up, restored, etc., including the addition of a new dome. When I went there with Isabelle just before Caroline’s wedding to Claudio, it all seemed in good condition but there was lots of litter around.

The biggest adventure was when we decided, at least Michael Fish decided, to go to Stanneth Woods. Again, Michael must have been told about them by his dad. There were three of us, Michael, who’d have been 10, Tony Collins a year younger, and me a year younger again. So off we went with our picnic; as usual, I had no idea where we were going; nothing was said, nothing was discussed. Anyway we eventually got to the Liverpool to Leeds canal at Feniscowles, a long way from home, on the way from Blackburn to Preston, always just rambling across country. And there we started to follow a coal barge that was moving along the canal at walking pace; decisions just seemed to make themselves. And we followed it, chatting a bit to the crew, for quite a long time. Then the decision to go home happened. No one had a watch and I certainly had no sense of the time. And so we went home. And it was very late. My mother would have been frantic with worry except that when she went over to the mothers of the others to say how worried she was, both of them said that Michael/Tony could look after himself, there was no need to worry, we’d be home in our own good time. Which is what happened. And that time I didn’t get a good hiding.

There’s no mention of Stanneth Woods when I search on the internet, nor if I try alternative spellings. But the other places, Old Aggie’s, Lyon’s Den, Hollinshead Hall, etc., are there and you can read all about them.

For some time, I think years rather than months, Michael Fish and Brian Holt spent much/all their spare time helping on a farm nearby, Upper Sunnyhurst Farm, owned by Bob Bailey. So I found myself well and truly excluded. It was a small dairy farm, with maybe two dozen dairy cows, some hens (no one said chickens in those days unless they were yellow, fluffy and the size of a baby hamster) and not much else. There was a Mrs Bailey, no children and a farm labourer called Jem Kitchen. (I remember seeing Jem soon after he’s had all his teeth pulled out, grinning away to expose a mouthful of gums.) They delivered milk every morning with a horse drawn milk float.

Our milk was similarly delivered by our milkman, Harry Bland, who owned the neighbouring Lower Sunnyhurst Farm, and also had about two dozen cows, some hens and not much else. From time to time he kept a bull calf in a shed in the dark, being raised for veal. (Occasionally his son John and I would get it out and stroke it or play with it, till an adult noticed, and then we’d get shouted at.) Harry Bland has a second wife, his first wife having died, a son John by his first wife and a daughter Beryl by his second wife and a farm labourer called Albert; Later I heard that one day Albert did something inexcusable and was sacked on the spot. Harry’s father, old John Bland also lived with them. John (young John) was a year or so younger than me and we were also good friends, and when I was excluded by Michael and Brian I spent a lot of time at Bland’s farm. (When Isabelle and I went to have a look just before Caroline got married to Claudio – on the way to the tower – in 2011?) the farm had been converted into a Bed and Breakfast place.

When I was 9, 10, 11, I was quite keen to be a farmer when I grew up, in fact. In the school holidays, John and I often helped with the milk round, which meant going round our side of Darwen with the milk float delivering milk on doorsteps – and collecting empties. It would start at maybe 8.30 or 9.00, (the cows having been milked, the milk cooled, etc., by then; I remember being impressed by how clean and orderly the dairy was, in contrast to the rest of the farm,) and would finish at 1.30 or 2;00 pm. Mostly, if I remember, the milk was in huge milk churns, from which it was decanted into 1 pint bottles as we went along, and closed with a cardboard milk top. (Collecting milk bottle tops, playing for them by seeing who could skim his the furthest, was also a regular craze.) Some people just put a jug on their doorstep and a pint or whatever of milk was poured in using a measure. There must have been four or five horse-drawn milk floats that came round every morning, seven days a week (I think). There were two or three docile cows at Bland’s farm that we had a go at milking from time to time – no milking machines then. (There were also some cows that were not docile at all, and awkward to milk. We kept well away from them). In the summer, i.e. not the winter, we would sometimes go to bring in the cows for the afternoon milking from whichever field they were in. In fact there was also a milk delivery up Sunnyhurst by the Palatine Dairy using a small lorry, and by the Co-op using an electric battery driven milk float.

I’ve also got memories of hay making. It was quite early in the summer, even June I think. The grass would be mowed, then turned over to help it dry, then arranged in rows ready for collecting. In those days, before 1947 and well after too, it was all done by machines pulled by horses. Bland’s had three horses at the time, Dolly, Betty, mares, and Jimmy a gelding. (That’s how I first learnt what a gelding is). Finally the hay was collected manually and loaded onto the hay cart. That as pretty heavy work using hay forks done be the men. When the hay cart was fully loaded up, it was taken to the barn to be unloaded (there were two barns I think, one part of the main farmhouse building, the other a Dutch barn, just a roof and with open sides.). No one was ever allowed a ride on the hay cart; this was considered dangerous I think. I can remember hay-making all day, which must have been during the weekend, and also late into the evenings (double summertime, so light until 11pm). We kids had to rake up all the hay that got left behind during the loading of the cart, and rake it as far as the next row to be loaded, so we were working steadily all the time. The breaks for a rest and a drink were much enjoyed but I don’t remember much about them.

You did see the facts of life, as it were, on the farm. From time to time a bull would be brought to make the cows whose turn it was pregnant. The action happened in a barricaded part of the farm yard and we kids were told to clear off. But we would sneak back to watch the action. The bull had amazing stamina.

John was not at all happy with his step-mother and told me regularly that she did not take much notice of him.

Going along the path past Bland’s farm, towards Tockholes, you first came to the waterman’s cottage, and then, set a good way back down on the right, a ruined farm, called Lower Wenshead Farm, which, with its land, was part of Bland’s farm. I think was the original farm that old John Bland had owned. We’d sometimes go there to play. It was easy to get into, but all boarded up and mostly dark. Once we (several of us) were playing there and we found the very decomposed body of a rabbit almost a skeleton, hanging from a rope that was fixed to a shelf. Someone pulled on the body and a huge heavy cutter from a hay mower came crashing down. If it had hit someone, I think it could have killed them. At the time we thought it was a booby trap, but now I think it was just the way someone found of hanging up the rabbit. In fact we saw rabbit’s bodies hung up to decay a few times, round and about there, mostly just hung on fences. I suppose someone shot them and left them there; rabbiting is a normal enough country occupation and rabbits were regarded as a pest. Further on there was Upper Wenshead Farm on the left, very isolated, not far from Old Aggie’s. The farmer was called Horsefield, and he had a son, an only child I think, called Oscar. He must have had a very lonely life, he came to play with us very occasionally, but it was a good walk from his home to Sunnyhurst; He was about the same age as Peter Fish and really big and strong, but he was always fun and never nasty. I don’t know where he went to school.