04/08/2015

Chapter 17 LRGS 1947-1949 What else, Part II?

There’s so much, it’s hard to know where to stop. So here are just a few more highlights – which may grow into a lot more detail; but I’ll try to make it interesting.

I just remember, the book that most impressed, really impressed me at that time, when I was 11 or 12 was a historical novel called “The Carved Cartoon”. I’ve just searched a bit about it on Google and it’s still available. What I remember most is the descriptions of the plague in London. I’ve just found two reader reviews on Amazon in my searching. One started something like, “Read it as a boy. Happy to read it again; A most pleasant read.” The other started, “What a load of codswallop…Walter Scott is concise and historically accurate in comparison…” So there you are. Anyway, at the time I just loved it. It was published in the SPCK (Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge) in 1896, so it must have been busy propagating Christianity; the name of the author is Austin Clare. I found it in the Storey House library – two shelves of books in the book-case in the Storey House sitting room.

From time to time the school was given an extra whole or half day’s holiday. There was one every year after Speech Day, the annual prize giving early in the school year. There was always an invited outside speaker, usually a “distinguished old boy”, who would end his speech by asking the headmaster to announce an extra half or whole day’s holiday (great cheers, but not from surprise). Also there would be an extra holiday for a royal wedding or other such occasion. For the boarders, this meant that the house masters or someone would have to organise something a bit special for us. I can remember one whole holiday in particular while I was still in Storey House. We were to go to climb a mountain called Ingleborough in the Yorkshire dales, 723 metres (2,372 ft) high. We must have been taken to the starting point, Ingleton village I think, by coach. I seem to remember that the matron, Miss Dugdale was one of the staff team that took us. It turned out to be a beautiful warm sunny day, it was certainly quite a stiff climb/walk, and I remember us all being very hot and thirsty. I can also remember how we kept thinking we’d nearly reached the top but then realising we’d just got to the top of a ridge and there was more to go. When we finally did get to the top, we were very pleased, and the views were marvellous, as was the picnic – so it seemed. There was a cairn of stones at the top, and a trigonometric point, which like everything else was new to me. This was the first time that I’d climbed a mountain. Incidentally, Ingleton village is the starting point for a lot of caving activities. The rock on which it stands is limestone and riddled (for all I know) with passages, caves, stalactites and stalagmites, streams, lakes and so on. It is certainly a famous centre for caving, or pot-holing, as it was called at the time by the various class-mates of mine who used to do this at weekends (not then; when we or rather they were sixteen or older). I could only wonder which was worse, pot holing or rock climbing.

All the boarders joined the School House scout troop, the 3rd Lancaster. I really liked the scouts very much, it was really my thing. I was in the Pheasant patrol and our first patrol leader was called Grave, always called Gravy. He was a superb swimmer, and all through school won every swimming race that there was to win. Ditto, at things like the Lancaster Inter-schools Swimming Gala, he would without fail win every race in his age group. And in relay races, if we were behind, he, always the last to swim in our team, would catch up the others and win even when the situation seems completely hopeless. Really amazing. Unfortunately, he was a Light Blue while I was a Dark blue. Come to think about it on re-reading, I now think he was a Dark Blue; it seems I was just in the mood to start a sentence with “Unfortunately”.

The boarders were divided into two houses for the purpose on sporting events in the school, Light and Dark Blues. In the 1930s they had all been the Blue house, but they always won everything and so got split in two. When I started at LRGS there were six day boy houses and the two boarder houses. But the boarder houses still won almost everything. Most day boys just weren’t so interested. In fact there were 117 boarders when I arrived in September 1947 and about 600 day boys, so the day boy houses were each about 100 boys while the boarder house would have been 58 and 59 or thereabouts. But the boarders still won almost everything. Today, 2015, the house system has been abandoned, I don’t know when but I think some time ago.

As I was saying, scouting was really my thing. I remember getting hold of Baden-Powell’s “Scouting for Boys” straight away when I joined at eleven, and just devouring it. There were some proposed boy scout exercises, and I faithfully did them every morning for months and months. I can still remember them. Always first thing in the morning, starting with long deep breaths. I really wanted to do everything perfectly, being observant, knowing all about wild animals, birds, trees and plants, knots and splices, being expert in all sorts of country craft, observing anything suspicious, understanding the weather, being courteous to women…

Fortunately, at scouts I didn’t have to be able to do thirty skips backwards with a skipping rope, which had been my great failure in the cubs, and so with much keenness, (keenness was the word) I passed all the tests to be a second class scout pretty quickly and then moved on to working for the first class badge and proficiency badges, swimming, first aid, interpreter… The thing is though, that you could only be in the scouts at LRGS for three years, because once you were fourteen you joined the C.C.F., the Combined Cadet Force, in effect just army cadets. It was at the same time as scouts each week (in fact, when I come to think about it, I don’t think it was) but anyway you couldn’t do both, so as with scouts at 11, all boarders joined the CCF at 14. Conscientious objectors were not tolerated. As with the scouts, I loved the CCF. The marching, the drilling, the shouting out of orders, the shooting, the exercises and field days, the making my boots so extremely shiny, ironing my trousers into razor creases, all the order and the structure… When I ask myself why? now, I really wonder. Perhaps just because I could do it, I was good at it and it was finite. In school with Latin and physics and history, everything was limitless.

As well as the weekly scout meetings (Thursday evenings I think) we all did a weekend sort-of camp each term, just Saturday and Sunday, one patrol at a time. The LRGS scouts rented/had the use of an old tower on the top of a hill; I think the nearest village was Nether Kellet, about ten miles from Lancaster. It was on four floors I think, with just one room on each floor. The third floor was the dormitory, with very primitive bunk beds. We washed in the nearby stream just down the hill; we also got our water from that stream. We cooked on a wood fire and there was a latrine of sorts. It would certainly have drained down-stream of the drinking water. We knew what we were doing. All very pioneering and very well organised. We would get there by bus from Lancaster followed by quite a hike. The patrol would travel independently of the scoutmaster, who would presumably have come by car and would be waiting for us. I often wondered how the patrol leader found the place; I had no idea and never thought of asking him. At the time I had a war-time rucksack of my dad’s, and the stuff we had to carry was quite heavy. It included a blanket and a sheet sleeping bag, also my dad’s from the war, with blanket pins. Anyway, it was not comfortable to carry, no frame or anything like that, and I was mighty glad each time I could take it off.

The scout master was called Mr Ingall; he was pretty young, a maths master, and after my first year, my house-master as well. He was very organised and we sometimes called him “Efficiency Ike” though his normal nickname was Inky – I think. It’s amazing how many times in these memories that I say something and then immediately have doubts about what I said… I really admired him a great deal. He was fair, well organised, keen as keen, just thoroughly kind and decent and at the same time pretty tough and demanding.

The times at the den were great; I loved every minute, apart from carrying that rucksack. The basics of living, cooking, eating, washing up, etc., the games, the instruction – the branches from which tree burn well/badly when it comes to making a fire; on Sunday morning there would be a short service on the roof (it had a wall round it so there was no great danger of falling off), referred to as a “Scouts own”.

The most memorable moment, when I stop to think now, is the time Don Fowler (my age, so 12 or 13 at the time) dropped a billy can full of eggs that he was carrying back from the local farm. I don’t think many were broken, but they were virtually all cracked, I would say. Anyway, for the rest of the weekend – and some time after – he was called Egbert.

I also went to two scout camps in successive years, for a week, immediately at the end of the summer term, so late July/early August. I think I didn’t go in 1948, so it would have been 1949 and 1950. Both years we went to the same camp site in the Lakes, near Ulpha, on the banks of the River Duddon, not far from Coniston, so Lancashire in those days. Again, it just loved every minute; at least that’s how I remember it now. I just loved the order, the good organisation, the keenness and efficiency, everyone one really seemed to be doing their best, whatever the activity. We had next to no equipment, no kayaks or such, but it was all great, even getting our tent and belongings laid out spick and span for the morning inspection. And there were hours long “wide games”, again so interesting and well planned and organised – as I remember. Everything was seen so positively. One evening we (the scout master) invited our neighbours round for a sing-song round the camp fire, another lot of scouts from a scout camp and, hold your breath, some guides from a guide camp. I had a long talk to one of those guides, about my age; it was… well I still remember today how excited and happy I was. Though there was no follow-up.

At the second of these scout camps, the scout master was the successor to Inky Ingal who had moved on, to another job I think. The new one was called Dimond, C. N. Dimond, always referred to as Charlie Dimond. He was a French teacher and taught me French in the fifth form. Also quite young, with a very pretty wife who was a guide leader. He was very different from Inky but also very good in his way. He knew lots of good clean songs for singing round the camp fire and could sing them, and get us to sing them really well, One fish ball, Green grow the rushes, …

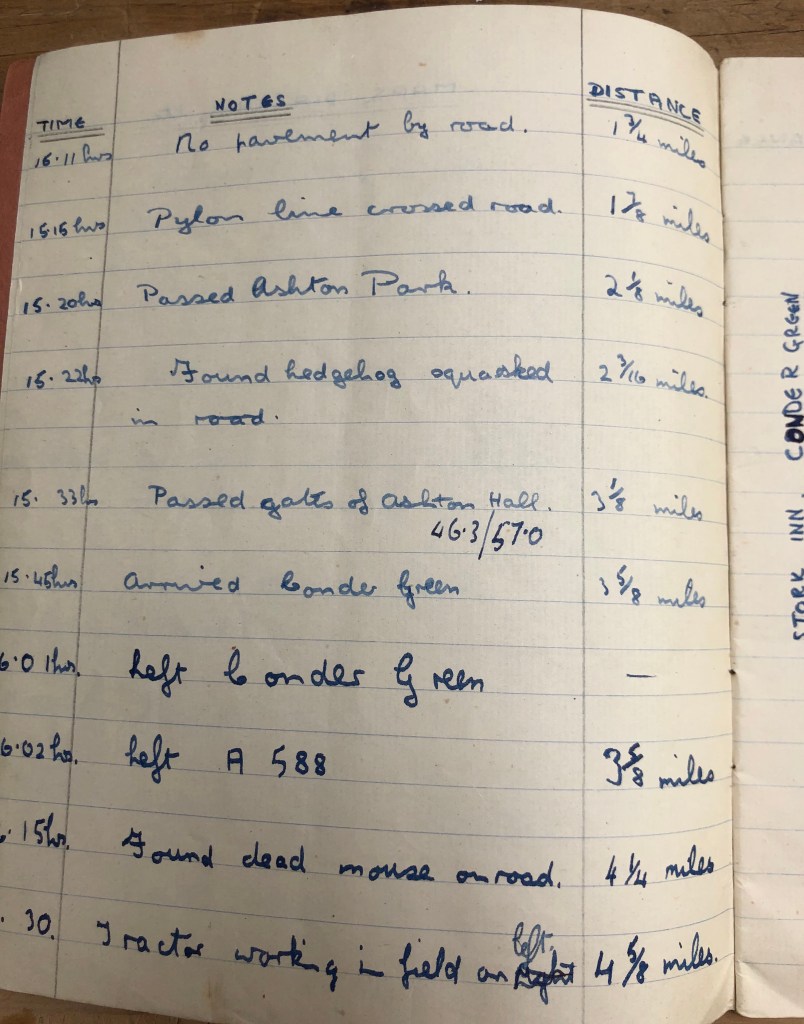

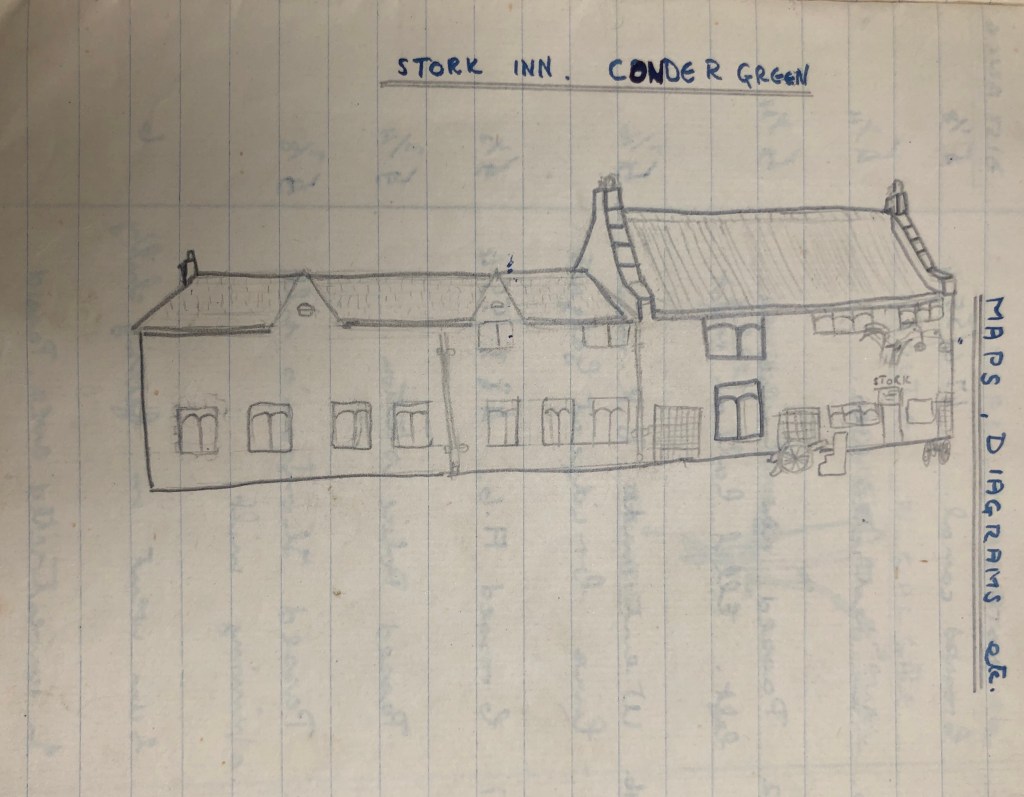

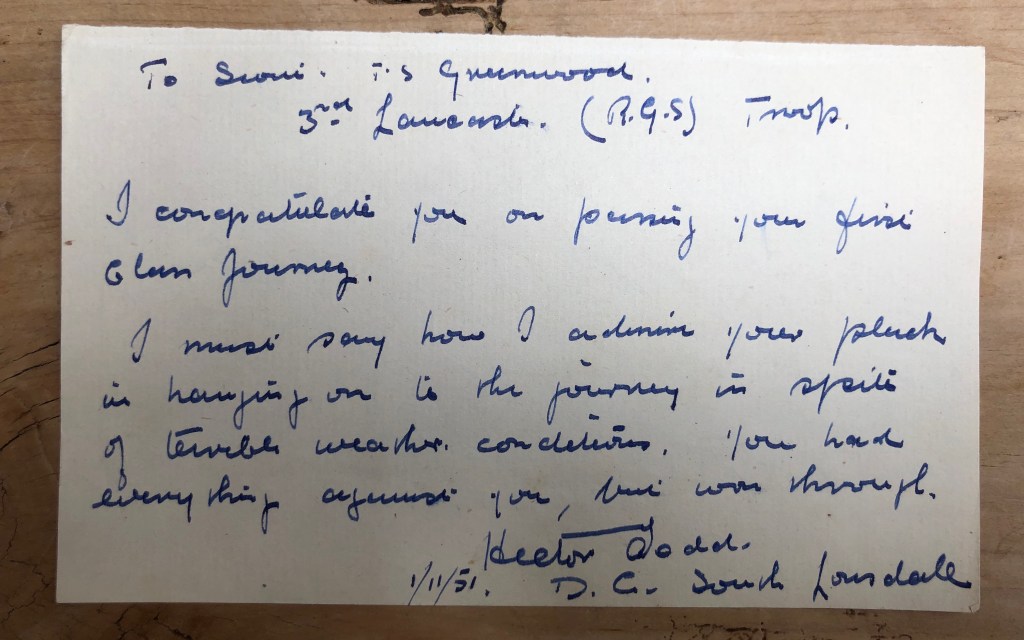

One final episode about scouting. The last test to become a First Class scout in those days was the so-called First Class journey. Two of you were sent off, from Saturday morning until Sunday afternoon, with rucksack fully loaded: tent, sleeping bag, cooking equipment, including enough matches, but no paraffin or other burner, food, etc., with a set of instructions to follow, showing a route, observations and sketches to make on your way, a reference to the place where you were to spend the night and so on. I went with a fellow called Alan Foster, who I always called Foster, my age, OK, but not a particular friend. It all went to plan, but on Saturday evening it started to rain and it rained a lot. We cooked our evening meal in the rain somehow, put up the tent in the rain, slept in the rain and got very wet in the night. At about ten p.m. Charlie Dimond arrived to see how things were, and suggesting that we might like to give up and try again at a later date. But we wouldn’t hear of it and finished the journey as per the instructions. I’ve still got the log that I wrote of that journey, including the remarks at the end made by the chief scout of Lancaster, one Hector Todd. (“Bravo! You had everything against you but you still won through!”) I won’t add, “or words to that effect”, because I’m going to scan that log book and attach it to this chapter, so you’ll be able to read the actual words. N.B. This is a hope not a promise.

Two points on re-reading this chapter. It’s very difficult to analyse one’s feelings as one (I) read(s) about really horrible things; like the great plague in London in that book “The Carved Cartoon”. It’s really awful to read about, all that sickness, dying, loss, pain, fear, grief, the carts taking away the corpses and dumping them in mass graves… There is such a mixture of real pain and suffering as one reads, combined with fascination and a sort of pleasure. And an intense gratitude that it wasn’t me. There’s a lot more to be said on this theme; books and films and museums and documentaries that depict horrors, Auschwitz, the Mafia, massacres of Armenians or Tutsis… attract and fascinate a lot of people; I suppose up to a point it’s legitimate, but too much is “sick” whatever that means; there’s a mediaeval castle right here in Seeboden, Austria, where I’m writing this, which has a museum depicting the tortures used in the middle ages – which we will most definitely not visit. (Taking you to the London Dungeon years ago was enough.)

And secondly, again, here’s a difficult theme or question even if not at all unpleasant. Did I like cubs, scouting, playing team games even when I was not much good, because I was naturally a team-player rather than a loner? Or did I become a team-player because of all those team activities? What does naturally mean? Or is being a team-player the normal, the default way to be? Do people grow up as loners because they’ve experienced a lot of rejection as children? Or as young adults? Our ancestors lived in small groups as hunter-gatherers for almost all our existence, for hundreds of thousands, even millions of years. We’ve been settled in villages, then towns, for no more than a few thousand years, possibly some tens of thousands. So perhaps being a team-player was the norm for everyone, men and women. Like with wolves and lions, it’s the non-dominant males who were driven out of the families/clans and became loners of necessity.

So, on to a few thoughts on special events at LRGS, which made their biggest impression on me in my first year or two.

Speech Day was an annual event, always held in the autumn, September or October I would guess, where people who had excelled -more or less – academically were awarded prizes. No doubt most schools have this sort of thing. Caroline and Johnny: were there speech days at your schools? I think I remember events at Cransley. But at MGS? Or MHSforG? Anyway, at LRGS it was always held on a Saturday afternoon (was it? I think so) in the Ashton Hall, the big meeting room/assembly room/hall in the town hall, where for example, the Hallé Orchestra gave their concerts when they came to Lancaster. And it was much the same in my first year, 1947, as in my last year, 1955. All the boarders had to be there, and lots of day boys (always called day-bugs when I was a junior) came as well. The parents of the prize winners usually turned up, you could say almost invariably, unless they were on station in Bangalore or somewhere (some of the boarders were at LRGS because their fathers were in the colonial service), so, as I as saying, the parents of the prize winners usually turned up, dressed in their best clothes, as also did the staff, wearing also their academic hoods and gowns and perhaps even mortar-boards in some cases. I can’t remember what came first, the speeches or the prizes, I really can’t. The harder I try to remember, the more unsure I get. Anyway, there was a speech from the headmaster, always RRT in my time (he became head in 1939 and retired when Jimmy was there (1957-1965 I think), so would guess in about 1960, to be succeeded by a Mr. Spencer. So the headmaster gave a speech to report on the previous year, with all the focus on the successes. (He used to say, but not at speech day, that his ambition for the school was for us (LRGS) to gain ten open scholarships at Oxford and Cambridge and for the first XV to beat Sedbergh School first XV at rugger, all in the same year. (At that time our school 1st XV only had a fixture against Sedbergh 2nd XV). Anyway, there was a self-congratulatory speech from the head, I think a speech from the Chairman of the Governors, and then a speech by the visiting speaker, as I’ve already said, almost always a “distinguished old boy” with the request for a half/whole holiday for the school at the end. In fact it was all good stuff, as good as could be expected, even if the school was far from perfect.

After the speeches, there was the award of the prizes, ascending from the humblest to the grandest. The prizes were all books, (perhaps there were some certificates where not enough money had been endowed) which in most/all? cases you could choose yourself. Prizes had been endowed for most subjects for every year, so there would be a second form Latin prize, then a third for Latin prize, … and on and on and on. The prize winners would go up onto the stage to collect their prizes from the visiting speaker so we all had to clap more or less non-stop for as long as it took, at least half an hour probably more. Towards the end, the top prizes were given out and the very clever people would get several, even lots. There was one prize the the most deserving boy who had not been awarded a prize. I only once won a prize, in my last full year, so at Speech Day 1954, and it was the prize for the best performance, i.e. exam marks, by someone in the Biology sixth. I asked for and got Mellor’s Inorganic Chemistry. I’ve still got it if ever you want to see it. (Caroline and Johnny and perhaps you grandchildren in 10, 20 or 30 years’ time – and you great-great grandchildren in 100 years’ time, the mind boggles: just remember that for every minute you spend reading this, I’ve spent 10 minutes or more typing; when your time comes to write down your memories for your children/grandchildren in 30?/50? years time, I trust that you’ll at least be good speedy typists; or perhaps you’ll just talk and the computer program will turn your speech into writing. Then your memories will be even longer than mine and no one will read them. Or perhaps a computer program will stick them into your descendants’ brains without their needing to read them). And towards the end of Speech Day, the Head of School would come to the front and call for and orchestrate three cheers for the visiting speaker, and the second Head Boy, three cheers for the school…

And so we come to Founder’s Day, apostrophe s not s apostrophe because at the time we were commemorating one founder, John Gardyner, who was said to have founded the school in 1472. A bloke, a boarder, a Scot, who went on to Jesus College, Cambridge, who was in the Upper Sixth when I arrived, called Athol Murray, later wrote a history of the school and discovered that the school was not founded by John Gardyner after all but that an older school had been re-endowed by John Gardyner in 1472. So now the foundation of the school is, we can say, lost in the mists of time. It seems to have existed in the thirteenth century but there is no record of when it was founded. But this “it”does seem to have existed continuously since then and LRGS does seem to be its direct successor. Until it moved to its present site in 1851, it was in Lancaster town centre near the castle.

Founder’s Day, as I remember it, and again, it hardly changed between 1947 and 1955, was two things that happened during the same weekend in mid-July. Firstly, on the Saturday morning there was a service in Lancaster Priory Church to give thanks to God for the foundation and continuing existence of the school and secondly, Old Lancastrians (OLs) were invited to the school that weekend and there were sports events, School v OLs at cricket, and in later years also at shooting, i.e. with rifles, golf, rowing, … plus the AGM of the OLs club and an OLs dinner. (These days, wives and girls friends are invited and the dinner is followed by a dance, all in the Ashton Hall. (I hasten to add “I think”).

The Founder’s Service was obligatory, after all it was in school time, and everyone was expected to wear a red rose in their buttonhole, and pretty well everyone did so. The boarders were all provided with red roses by the Headmaster’s wife. During the service the school song was sung, not at all ancient, written I would guess in the 1930s. Imaging singing:

“So here’s to the Red Rose

The Lancaster Red Rose,

Old John of Gaunt’s Red Rose,

The Royal School’s Red Rose…”

I could continue. There are worse school songs no doubt. And it has its own original tune, not just the tune of “Oh come all ye faithful” like Queen Elisabeth’s Grammar School, Blackburn (QEGS)’s school song. Anyway, I liked the idea of a Founder’s Day. I liked the service each year, even singing the school song. And don’t forget that at that time there had only been one Queen Elizabeth, and King George VI was still alive. So QEGS saw itself as an ancient foundation. And as I think I mentioned, Michael Fish went there because he failed the 11+ and at that time you could still go there as a fee paying basis if you’d failed the 11+.

And now, a few words about the Boarders’ Feast. The approach of the end of term was always a time of great excitement and built up to a fever pitch at LRGS, especially if you were a boarder, even more especially if you were in Storey House, and even more if Christmas was coming soon. The highest point of all was the Boarders’ Feast. Part of the culture was that everyone behaved as if home was pure bliss, where everything was perfect. Weeks before the end of term we drew charts marking the number of hours till the end of term, and every few hours announcing how many were still left. We put on our own Christmas Concert in Storey House, and Miss Dugdale really was great, teaching us Christmas songs which were new to us, encouraging us to produce sketches, telling stories.

Packing our trunks, then seeing them being taken away by the railway or road carrier was also a source of much excitement, because home sweet home was so wonderful.

The boarders’ feast was on the last night of term, I think, and from about the time that school finished at 4.15 until we were allowed to go up to the boarders’ dining hall, at – I don’t know – 7 o’clock, say, my abiding memory is of us all endlessly brushing our hair and putting more and more Brylcreem on, to look as smart as possible. The meal was always the same, sausages and mash, followed by Christmas pudding and custard. The thing that was different was that you could eat as much as you wanted. The sausages were inexhaustible. I remember that Laurie Guy claimed to have eaten 18 once. I wasn’t far behind in those first two or three years. They were made in the oven, so roasted not fried, and they were OK, even delicious. There were silver threepenny bits in the Christmas pudding but we had to give give them back in exchange for ordinary twelve sided copper (cupro-nickel?) ones, because by then silver threepenny bits had long been out of circulation – since 1937 I would say. After we’d eaten there’d be an entertainment. I can only remember that the prefects always put on a song.

One year the prefects wrote and performed a song, to the tune of “Irene good night” with a chorus which went, “We toed the line, (x3) and kept from crime, and now we’re all house pre’s.” And we all knew what a lot of lies it was, how hypocritical, because we knew what really went on, smoking, meeting girls, breaking bounds…

On the last day of term, there was a final assembly in the middle of the morning, and we all sang, “Lord dismiss us with thy blessing…”, and the lessons was always from Philippians 4, “… whatsoever is true, whatsoever is honourable, whatsoever is just …”

And that was it. We’re all heading home. Apart from the people who were travelling a long way, like to London, who left earlier to catch their train. Some lucky people, but not me, were collected by a parent by car. To start with, I went home by train but I soon switched going by to bus; there was a Ribble bus direct from Lancaster to Blackburn which I went on in those early years. It took two hours to do 30 miles, but was much cheaper and direct; no need to change in Preston. (From the age of 14 or so I hitch hiked, which was always easy and never a problem, and much quicker than the bus).

Holidays! I need to say something about the school holidays, don’t I? Perhaps that had better be What else Part III.