2012-11-01

Tom memoirs Part III, 1936 up to 1945, the end of the war

So here I am, born 16 September 1936, at, I think around 9.30 a.m., in a maternity clinic in Vienna. I have no information about how my Mum’s pregnancy went, but I don’t think anything dramatic happened. When I was just new born, I had a long head, and my father told my mother not to worry, I could always wear a hat to avoid looking peculiar.

My Uncle Oscar, I think (in fact I’m pretty sure) the husband of Hedi, my Mum’s cousin, wrote a horoscope for me, based on the exact position of the planets or whatever mattered at the moment of my birth. I can remember seeing it when I was small; it was in a purple covered exercise book and contained diagrams as well as text. Then it vanished; I suppose my mother threw it out. I’ve still got another seemingly identical purple covered exercise book that was the log of my first days/weeks on earth. For each day it gives what I consumed (quite a lot of tea I think – in fact I’m sure), plus my bowel movements, my weight (every day?), etc., and any noteworthy comments. It must be in the cellar here; I will get round to digging it out.

While I really don’t believe in horoscopes, it’s worth mentioning the bits that I remember, things that my mother mentioned; it was in German and I never read it. It said that I would live to a good old age, that I would have an unhappy first marriage and a happier second one. And that I would have a career somehow related to water. That’s all. My years at Buss and Biazzi were mainly to do with hydrogenation equipment and hydrogen, in German, is Wasserstoff. Just fancy that!

When I was tiny, I couldn’t keep any food down and this became a big worry. The specialist who was called in said that one of the sphincters in my stomach was not opening so nothing could pass through. They were close to deciding that surgery would be needed – it could easily have killed me I guess – but then, either thanks to some treatment or just anyway, things got better. It may all be logged in that purple backed exercise book. The last entry is written by one of the nurses, and says, “Good-bye dear little Tomi, I hope you will have a wonderful life …”, or words to that effect.

And then I was living with my parents, my mother’s parents and Hilda at Hietzingerhauptstrasse 95. I have no memories of this, but I can say that I was taken for walks in my pram, later in my push-chair, round Hietzing, including the grounds of Schönbrunn Palace; there are also photographs of me playing on the Roten Berg.

There are one or two episodes that I was told about. One day, when I was just close to being able to walk, so just under 12 months (I was an early walker), I put my hands onto an unguarded hot stove (we later had it in Darwen so I can remember it very well), and it was so hot that my hands stuck to it; so, I was badly burnt. I was told that I screamed a lot at the time – who wouldn’t have? but clearly I did not suffer any long term effects, I’m glad to say.

The worst (worst?) thing I did as a toddler was to open a drawer where my dad had put a set of newly purchased stamps that he’d just bought for his collection and to mangle them up so as to be worthless. They were the FIS (Federation Internationale de Ski) stamps issued by the Austrian post office to commemorate a skiing competition in Innsbruck in 1933. I just searched for them on Google and here they are, today’s price 600 €. As they were issued in 1933, they were presumably already collectors items in 1938 when I committed my first crime. My dad repeated the story, with much sorrow, certainly more that three times that I can remember.

My mother also told me that once there were some German military aircraft (the Luftwaffe, no less) flying over Vienna, and I pointed to them and said, “Pipi oben”, meaning “Birdies up there”. She told me that she found a child’s innocence when seeing those bombers, or whatever, very upsetting.

Once it had been decided that we were moving to England, when I’d have been around 20-22 months old, my mother remembered asking me, in German, “Where is Tomi going,?” and I answered seriously and solemnly “England”. “And what will Tomi be then?” And I answered, “Engländer.” (Englishman).

And that is, I think, all I can tell you about my life in Austria.

You can read up about the build-up to the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938 in the history books (or for example on Wikipedia). Until then, the situation of the Jews in Germany was known in Austria, so a lot of Jews were soon planning to leave. (The Hornemann’s left Berlin in the mid 1930s initially for Brazil and moved to London some time (a year or two?) later). As I’ve told you, one of my dad’s friends came to visit him, I suppose in March or April, wearing a brand new (let’s imagine) SS uniform, I think where he worked, and told him that he absolutely had to leave as soon as possible, and there was certainly no future for him in Austria, (by now the Ostmark province of Greater Germany).

So anyway, my dad was in London two months later (having a Czechoslovak passport not an Austrian one, i.e. by then a German one, made things easier). Several of his friends, all in their late 20s, (my dad turned 29 that May) were also there, I can name Miki Weiner and Franz Barta whom we saw, with their wives and kids, from time to time after the war. They all needed to find someone to sponsor them and vouch for their good character, as well as a job. There was an organisation in London to help Jewish refugees and to coordinate contacts between prospective employers and hopeful applicants … and so, thanks to his being able to say that he had experience with manufacturing plastics products, my dad found himself with a job to set up and run a factory to make plastics umbrella handles in Darwen Lancs. The fellow who hired him was somehow in the umbrella business, he was called Hoyland, and the company came to be called Celco.

So then presumably he contacted my mother and the organised the great departure for my mother and me. We travelled by train from Vienna to Ostend; we needed a visa for the UK but with a Czechoslovak passport, presumably not a transit visa for Belgium. Then we crossed to Dover on my second birthday; the passport I’ve got is stamped 16 Sept 1938. And then on to London. My mother mentioned that on the boat I was running up and down wearing a pink coat. Once we were in England, my mother had it dyed navy blue. I can remember that coat both when it was navy blue and also when it was pink. I can still remember exactly what shade of pink it was. That may be my earliest memory, come to think about it. And to be pedantic for a moment, human being are not good at remembering exact shades of colour.

There was not much money to pay for the move, and Willi Kaufmann helped a lot. My dad also sold all the best stamps in his stamp collection to raise some cash; the only one I remember him mentioning is a commemorative stamp for Chancellor Engelbert Dolfuss who was murdered by Austrian Nazis in 1934. Here it is; I’ve just seen it offered for sale on line (in 2012) in mint, never hinged condition, as my dad doubtless had it, for US$ 649. Again, you can read about Dollfuss and all the political travails in 1930s Austria on Wikipedia.

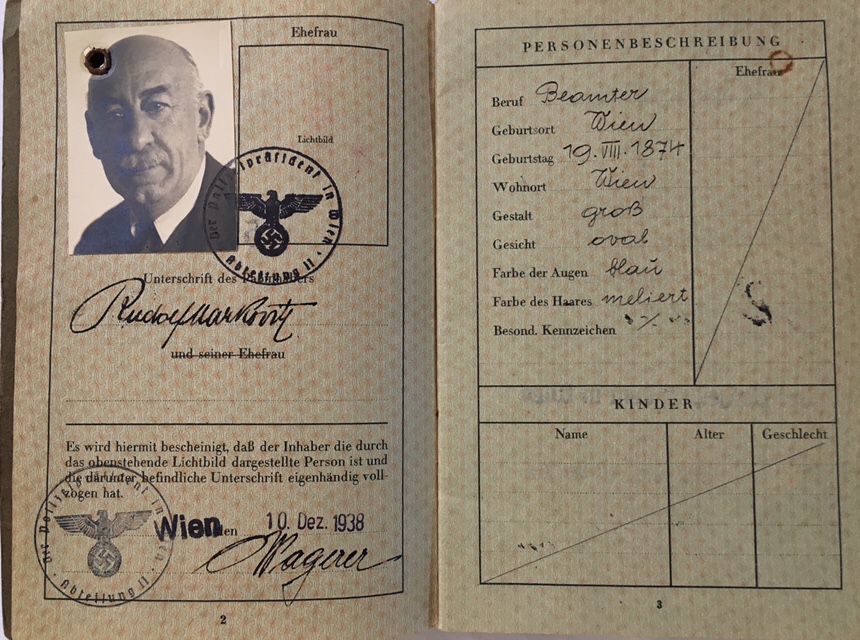

So, my mother and I left Vienna in September 1938, and my mother’s parents then followed us, I guess as quickly as possible. By then Austria was part of Germany so they had to get/have German passports. I’ve still got my grandfather’s – see below – and from there you can work out the drama of their journey; how they first got to the German/Belgian border on 12 January 1939 and were refused admission to Belgium because they did not have transit visas for Belgium. So they had to return to Vienna to get their transit visas. Then you can see the Belgian transit visa was added on 3 March 1939 in Vienna, and then there are the stamps for crossing Belgium (illegible) and arriving in Dover on 17 April 1939.

Here’s Rudolf’s passport, the front cover and pages 1 to 3, slightly reduced in size to get it on one page.

I don’t know much about what happened next. I don’t know if we stayed in London or just when we arrived in Darwen. Perhaps or even probably before my grandparents arrived, but I don’t know.

So the next section is called: DARWEN

Actual, I think I ought to say something at this point about what happened to the rest of our family after the take-over of Austria by Nazi Germany.

My dad’s older brother Walter, married to Illa (short for Illona, the first woman ever to get a degree in engineering at Vienna University), got their kids, Fred – called Friedl at the time – and Hanna, to England and then returned to Vienna to work with the Kindertransporte effort– there’s lots of information if you Google Kindertransporte – to get Jewish children out of Austria, before turning up in England some time before the war started (3 Sept 1939). Fred and Hanna, who would have been about 12 and 10 at the time were fostered with a Quaker family in the north east till Walter arrived. Illa and Walter separated at some point and Illa finished up in Palestine – with another bloke I think. Walter and the kids went to the U.S.A. pretty soon, (in 1939?) After the war Illa and Walter got together again (remarried?). (JG adds – there’s a great letter from Fred to Tom when Otto died, which gives lots of good detail about Fred and Hanna’s visit to Darwen in the early period of the war – I’ll upload it as an appendix)

Edith was married to Hans Weiss who organised for her to go to Italy. He stayed in Austria and was part of the anti-Nazi resistance (he was in a royalist group) and was killed by the Nazis. Edith was left to fend for herself and found her way to Switzerland when Italy joined the war on the German side. It was there that she got to know/live with?/work for? the Delachaux family which included Jonny whom she later married, when she was about 42 and he was about 24, so just after the war finished.

Peter was 18 in 1938 and found his way to France when the war started. (Lisl did not get to know him till 1940 when they met in London. She is pretty vague when I ask her what happened to Peter between 1938 and 1940). Anyway, Peter was in France, possibly in the French army, and after the fall of France in June 1940 he managed to get to Marseilles(?), then North Africa, then Gibraltar, then London. Everyone, i.e. my dad, feared that he’s been killed and there was great rejoicing when a telegram arrived from Peter from Gibraltar, saying that he was well and coming to London.

My dad’s mother also got to England in 1938/9 and most of his family, uncles, aunts, cousins, etc, escaped, to England, Australia, Palestine … The only exception that I know about was Onkel Emil, my dad’s mother’s brother who I think had never married. My dad told me that he committed suicide in Austria when the war started and he realised he would not be able to leave.

On my mother’s side, you know Fritzi and Eva’s story well enough. I know that one of Rudolf’s sisters, Fanni and family escaped to Canada. Eva told me recently that they got their money out of Austria and were well off, but there was very little or no contact after the war. The family of Rudolf’s brother, Edmond, notably his two sons Harry and Freddy spent the war in Palestine. Harry and family stayed and became Israelis; Freddy moved back to Vienna after the war.

We knew Rudolf’s other sister Lina’s daughter Litty (Melita) who also got to England before the war. She was married to a non-Jew, Robert Kloss, who divorced her when the Nazis arrived. My mother told me that she was pregnant at the time and had an (illegal) abortion, because she didn’t want to risk having a child when the situation was so uncertain.

Concerning my mother’s family on her mother Helene’s side, I’ve got the text of 26 pages, given to me by Eva, the memories of Lilly, the daughter (and only child) of Helene’s younger sister Ida. This gives a lot of information about the family and ought to be appended to this really so that I don’t have to repeat everything she says. Ida and second husband Will got to the U.S.A. via Cuba but did not leave Vienna until November 1941, Lilly and husband Leo went to France when the Nazis took over Austria, had a terrible time there, but finally got to Lisbon and then to New York, arriving in April 1941.

I don’t know what happened to Helene’s older sister Paula; I know she died of cancer, perhaps before the war. She had two daughters, Hedy and Marianne; Hedy also got to the U.S.A. (she had no children) but Marianne and her daughter Monica didn’t escape. Marianne’s husband went to London on his own like my dad, looking for work and immigration papers, but he met another woman there, and just abandoned Marianne. There’s a letter from Marianne, written from Poland to my grandmother dated ?1940/1? which I recently lent to Eva, saying that they’re in a camp but OK – no doubt the letter was censored – but I guess they were gassed soon afterwards.

Helene’s brother Ernst (the youngest of the four) also got to London with his wife Dorle and daughter Gerty. Ernst was a lawyer and had been arrested and pretty badly mistreated by the Nazis and then released. I was told that he died as a result of this mistreatment soon after arriving in England.

There were a lot of other relatives of my grandmother Helene about, lots of Brandl’s including Minni who was sent to Auschwitz, worked as a nurse under Dr Mengele and helped, probably saved, Fritzi and Eva, and survived herself. I think quite a lot of Brandl’s didn’t survive the war. (Hans Brandl was in the Czech army and came to visit us in Darwen once or twice). Another (second) cousin of my mother’s on her mother’s side was Annie Sgalitzer who was about my mother’s age a lovely person, a nurse, who married a rather weedy Englishman called Frank Yates. They lived in Walsall, and I used to go to have supper with them from time to time when I was working in Birmingham.