Memoirs of Tomas Stefan Greenwood

started 3 Feb 2012

Introductory quotation, from the Economist: 10-16 November 2012, p 78; from the review of The Scientists: A Family Romance, by Marco Roth. This book is the true story of the death of the author’s father from AIDS which he caught accidentally in his laboratory as a result of pricking himself with a needle that had been infected by a diseased blood donor.

In the concluding paragraph of his review, the anonymous reviewer writes, “All memoirs are, in their way, works of therapy; opportunities to air grievances and to cauterise wounds. So it is with this sentimental and confused journey, which offers no big revelations or pat conclusions.”

Will my memoirs be any different?

4/2/12

Part 1 My great grandparents and their generation. My grandparents and their generation

To start:

Let’s start with my grandparents where I have a lot of memories up to December 1963 when the last of them, my grandmother Helene, died.

My father’s parents: Ignaz (1873- 16 Dec 1928) and Franzeska, née Eckstein, called Franzi, (1875 – 1959); [my Dad said that when Peter her youngest child was born in (January) 1920 she was 47]; she died aged 85 I think; she’s buried in a cemetery in Monza, Italy – where the car racing track is. We went there once to see her grave; it must have been in the summer of 1964, the last time I went on holiday with my parents and Jimmy – I’d have been 27.

My mother’s parents: Rudolf Markovits (19 Aug 1874 – 3? January – early Jan anyway – 1951) and Helene née Schubert (17 Sept 1879 – 1 Dec 1963)

Ignaz Gruenwald

I have no memories of my father’s father Ignaz who died about eight years before I was born. I can only mention the things my father told me about him. I was never told anything about him by the other people I knew who had memories of him, i.e. Franzi, Edith (26 when he died) and Peter (8 when he died).

He was a very heavy cigarette smoker (my Dad said 60 a day, but I don’t suppose he ever counted them) and my Dad always said he died of nicotine poisoning; in fact, I think he died of a stroke. Somewhere I’ve got a condolence book, in German and Hebrew, with some information about his death and a newspaper cutting of the death announcement.

So … found it. It’s called Trauer Album and it has 24 printed pages, mostly in German with a few bits of Hebrew, mostly prayers. The only thing specific is the first page which is filled in with the name, Ignaz Grünwald, age, “in his 56th year”, date of death, 16 December 1928 and date of burial, 19 December 1928. Also a table on p.2, listing the date each year from 1930 until 1979 on which a commemorative candle should be lit. Also, loose in this album, the death notices torn out of the newspaper, the Neue Freie Presse of 18 December 1928, one from the family, the other from his company, the Metall- und Zelluloidewarenfabrik P. Grünwald. In the family notice, the family is listed as:- Franzi Grünwald, wife (Gattin), Walter und Illa Grünwald, Edith Steuermann geb. Grünwald, and Otto and Peterl, the children. The name P. Grünwald in the company name may refer to Ignaz’s mother Pauline Grünwald.

Ignaz had several brothers and sister, and my Dad used to enjoy relating how they all died, prematurely and in various unfortunate ways. More of that later.

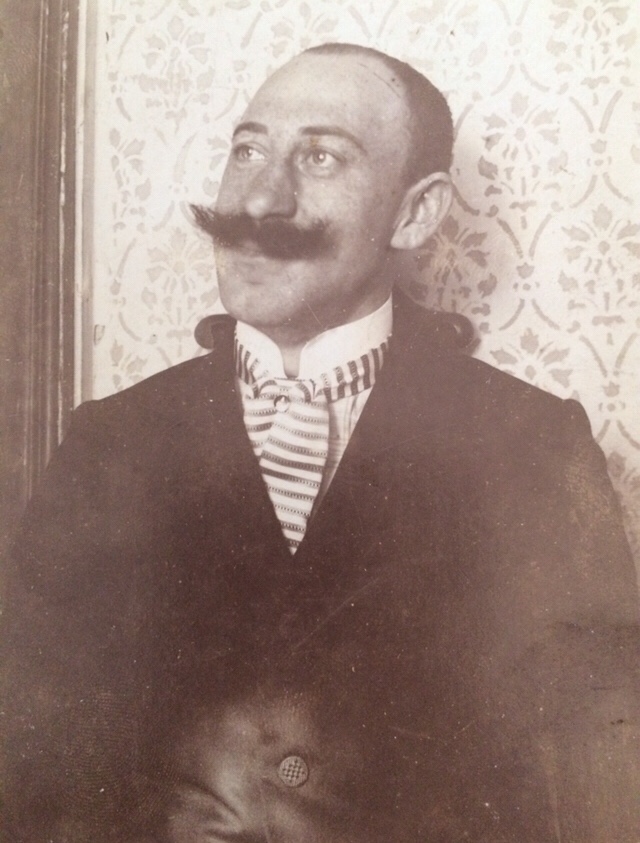

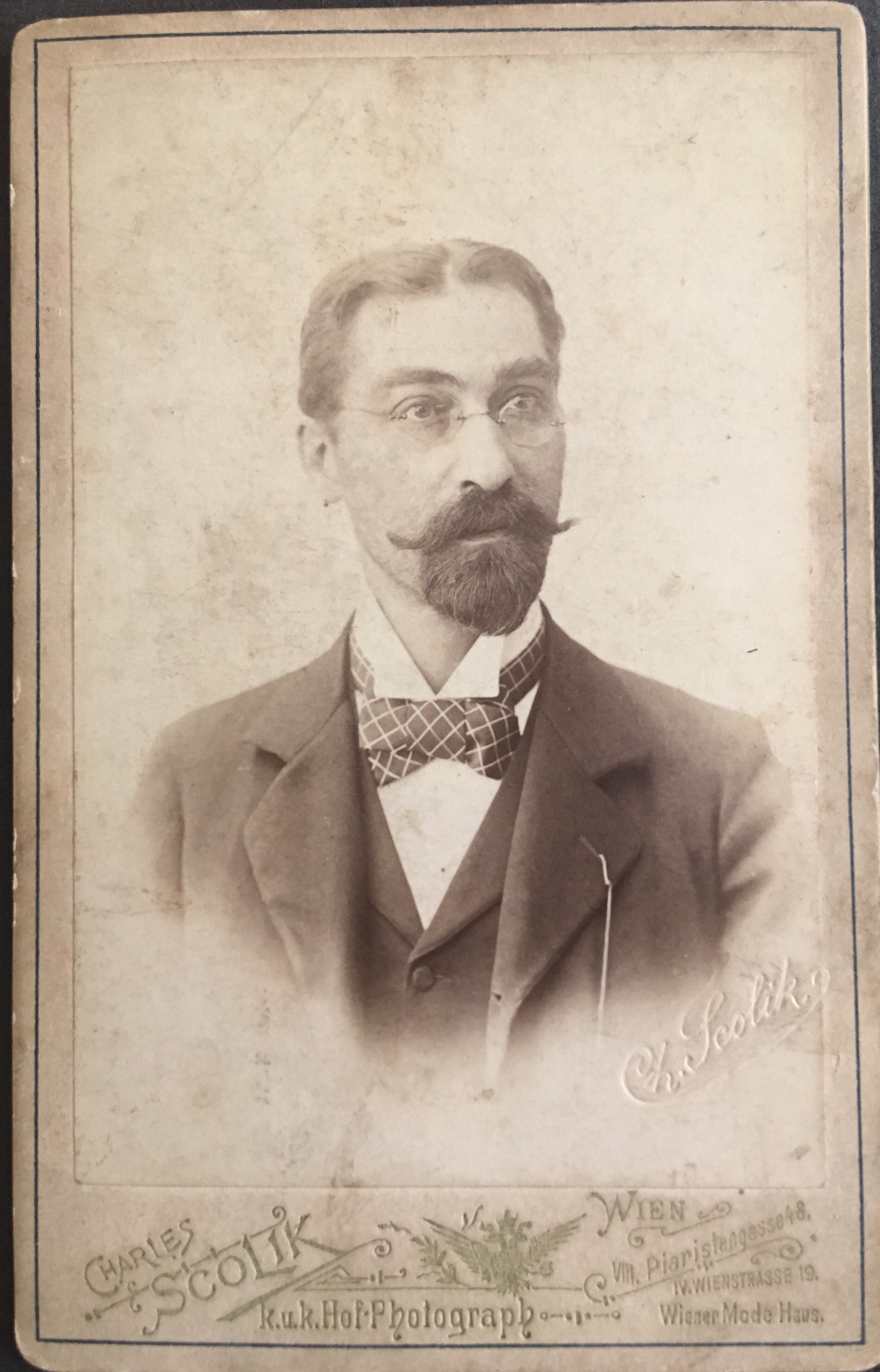

Photographs of Ignaz:

I can say very little about his personality. My Dad said that he was very strict with his children and he (my Dad) liked to tell how you had to eat everything that was put in from of you at mealtimes and what you left was served up at the next meal; but my Dad was more interested in telling a good story than in being strictly accurate. When Edith began to be interested in boys she used to sneak out without her parents’ permission and my Dad used to wait up for her when she came back, with the door bolted and would only let her in if she paid him. Maybe another good story. He repeated it more than once in Edith’s presence and she didn’t seem to disagree.

Below – Photograph of Franzeska, Walter, Edith and Otto around 1914.

My dad, years ago, gave me a tie pin which had belonged to Ignaz. It was a long pin, maybe 4 inches long with a precious? stone (or stones) all small at the top. You pushed the pin vertically through your tie to pin it to your shirt. I think this Ignaz is wearing it in one of the photographs we have of him.

Edith got married, it seems very young and very hastily, to a fellow called Max Steuermann, and apparently Ignaz set him up with a mirror factory in Zagreb. After that, all my Dad told me was that the factory quickly went bust and Max Steuermann, said to be a good-for-nothing, disappeared.

An anecdote about Edith; in her youth she apparently – according to my Dad – rebuffed the advances of Vic Oliver, a Viennese Jew, who also came to the UK just before the war, and became a well known actor and comedian from the 1940s till the 1960s.

Dad also mentioned that there were regular musical evenings in the family home when he was young, (so before 1928 when he turned 19). I don’t know if Ignaz played an instrument; none was even mentioned. And also that there was regular entertainment with lots of guests to dinner.

I only ever heard negative things about the marriage of Franzi and Ignaz. It seems that Franzi was very extravagant and irresponsible with money which caused big problems and also she seems to have had affairs with other men.

The first time that we went to Vienna as a family, my parents, my brother Jimmy and me, was in summer 1953 (or 1954?), and my Dad took us to see the house where he had lived as a child. I don’t know where it is, though Fred Greenwood knew. I just remember a big detached corner house with a garden in a quiet residential suburb; and that the name of the street had been changed since my Dad lived there.

My Dad also said that Ignaz once won a plum (or apricot) dumpling (Zwetschgenknoedel or Marilenknoedel) eating contest.

When Austro-Hungary was broken up after the defeat in 1918, it seems that people could choose their new nationality according to their origins, and presumably Ignaz was the key decision maker in choosing Czechoslovak nationality for the family. I don’t know why. Of the several 100,000 Jews living in Vienna in 1938, I think that most traced their ancestors to what became Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland (the part of Austria that became part of Poland in 1918 was Galicia I think), Yugoslavia, … The Czech passport with which my mother and I came to Britain in 1938 gives our Droit de domicile (in Czechoslovak, French and German) as Svitavka Boskovice; I was told that this is in what is now Slovakia; looking at Google though, Svitavka and Boskovice are shown as two towns or villages, 4 km (2 ½ miles) apart in the Czech Republic, north of Brno. As you know Jews were not permitted to live in Vienna till after the revolution in 1848, so I guess that this means that none of my great grandparents were born in Vienna; they would have been born in the 1840s and 1850s. I also read that Jews were granted full rights to citizenship in Vienna in 1867, and that after this, there was a big influx of Jews from elsewhere, mainly Hungary, Czechoslovakia, etc. In the late 19th century, Budapest had a large Jewish population and some people who didn’t like this insisted in calling it Judapest.

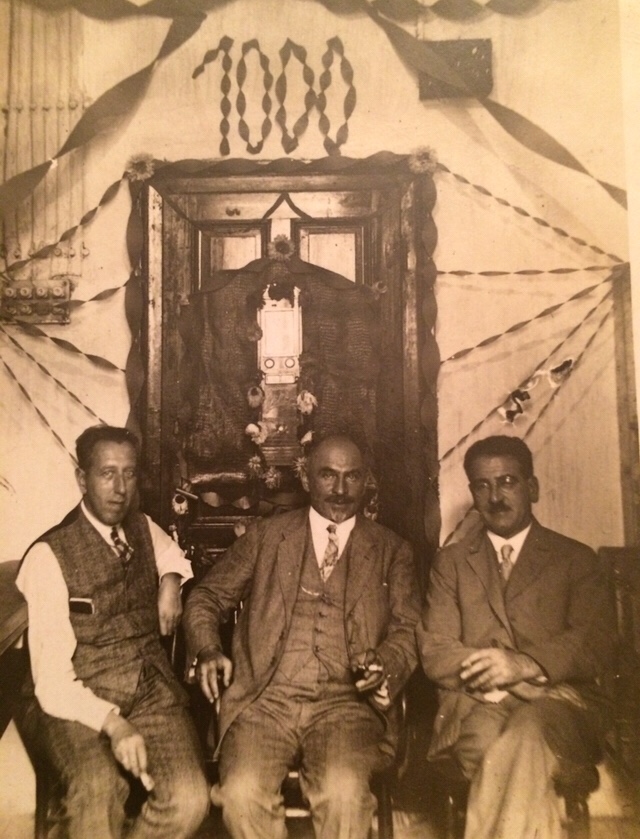

Ignaz owned a metal working factory, which may previously have belonged to his father Moritz Gruenwald. The only thing that I know they made was vending machines for confectionery (chocolate, etc.) and cigarettes. There’s a photograph in existence of Ignaz and Onkel Emil, Franzi’s brother sitting with a customer by the 100th – or 1000th – machine that the customer had just bought.

Ignaz had business contacts with Erich Hornemann’s father in Berlin and my Dad spent time in Berlin working for/with old man Hornemann, maybe as a trainee of some sort for a time. My Dad said that he and Erich became friends at 16 or so, i.e. around 1925.

Paternal great grandparents

Ignaz’s parents

Moritz Gruenwald and Pauline née Loew-Baer

Moritz: had a small (?) business as a sheet-metal worker/tinsmith (Spengler in German); at one time they made reproduction suits of mediaeval armour for which there was then a vogue. It’s possible that he already had business contacts with the Hornemanns in Berlin. He died before my Dad was born (1909).

Pauline: my Dad said he remembered her as a rather grand and imposing lady. Also he said that she was referred to as “the large grandmother” (die grosse Grossmama) in contrast to Franziska’s mother (die kleine Grossmama).

Their children, from oldest to youngest, I think:

1/ Ignaz

2/ Helene, married to a German Hans Heimann, who worked in a bank; had one son; died in childbirth.

3/ Klara, married to Dr Josef Koenigstein who was a lawyer;. had one son Robert; she committed suicide in the 1920s after a financial disaster.

Robert emigrated to Australia after Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938 and changed the family name to Kingston; his wife was called Audrey; my Dad had contact with them in the 1960s and 1970s; he died in 1989. There were/are two or three children.

4/ Wilma, never married, a professional pianist; committed suicide after an unhappy love affair in the 1920s?, using potassium cyanide from the metal treatment plant in Ignaz’s factory.

5/ Willi, never married; epileptic, my Dad sometimes said it was the result of being kicked on the head by a horse and/or falling off a penny-farthing bicycle; drowned in the bath during an epileptic attack.

6/ Elsa, married Joseph Harrer, a teacher and a Catholic. She died of gangrene after cutting herself with a knife whilst working in the kitchen; my Dad told this as a terrible story; first she had to have her finger amputated, then her hand, then her arm, but then the gangrene was still there and it killed her.

Elsa and Joseph had a daughter, Ilse, who came to the UK, presumably in 1938. Her married name was Bachrach and we knew her in London, (as a widow). She worked for a coffee trading company before she retired. She died around 1990.

Ilse had a son, Martin who also lived/lives in London and whom we also met; he was single. (There is no Martin Bachrach in the London area telephone directory, but one in Surrey).

Franzeska’s parents

Ignaz Eckstein and Therese née Antscherl

Ignaz was Head-postmaster (Oberpostkontrolleur) in Vienna. Dad said he was for a time the chess champion of Austria.

Died in 1914/1915.

Therese was small – see above – and certainly I remember that Franzi was small. Therese was the younger sister of a Dr Salomon Antscherl (died 1924) who came from Svitavka in the Czech republic. We knew his grand-daughter Helli who was my parents generation and lived in London. Her married name was Holzer I think, changed to Holder or something similar when they became British citizens. Helli died some time ago (1990s?); I met her one or twice at Tall Trees. Her children/grandchildren are around, perhaps in the London area. (Lisl may know more).

Apart from Franzi, there were two sons, Karl and Emil.

Karl died in the 1930s, was married to a woman called Mina, and they had one son, Egon.

Emil was married; his wife was called Minnie, and they had one son, Paul who was an optician. My Dad referred to him as “der Onkel mit dem langen Gesicht” – the uncle with the long face. He worked for his brother-in-law, my father’s father Ignaz. As I said above, there’s a photograph somewhere of Ignaz, Emil and a customer of theirs standing by a vending machine that the customer had bought.

My Dad once told me that Emil committed suicide – well (?) after the Nazi occupation in 1938, when he realised he would not be able to get out of Austria. On another occasion I was just told that he perished in the Shoah.

Franzi, Dad’s mother, lived with us in Darwen for a time soon (?) after we/she arrived in England. She was very difficult and there were a lot of quarrels. On one occasion, I remember that she threw an aluminium kettle lid at my mother’s mother, Helene, and it hit her on the forehead and caused a slight cut. There were three bedrooms in the Darwen house, one each for my parents and my mother’s parents, so Franzi slept in my bedroom, always called the nursery (Kinderzimmer). In fact, I don’t think she was with us long; it was just not possible nor practical. I remember visiting her with my parents, presumably soon after she moved out; she was then living in a rented room in Blackburn. After that, I don’t think I ever saw her again; I think she moved to London to be near Peter and Lisl (just Lisl when Peter joined the Czech army, I guess in 1941). They were certainly very hard up and had to live very simply. The big problem was that Franzi suffered more and more from paranoia. I remember hearing that she insisted that she could hear noises under her floor in the night and it was caused by the Germans digging invasion tunnels under England. After the war she went to live in Italy, presumably in the Milan area. Edith seems to have taken responsibility for her but she spent many years/all the time? in a psychiatric hospital. When my parents went to see her in the early 1950s while we were on holiday nearby, they wouldn’t let me come with them. They said that she was in such a bad way that it would be too upsetting for me.

So my only memories of Franzi are from when I was three or four. She was always very kind with me. She was the first person to say a prayer with me at bedtime. It was:-

Müde bin ich, geh’ zur Ruh’,

Schließe beide Äuglein zu;

Vater, laß die Augen dein

Über meinem Bette sein!

I just looked it up in Google Austria/Wikipedia. It’s by Luise Hensel, a German 19th century writer and poet. There are four verses but I only have memories of this first one. There is even an English translation – it’s said to be one of her best known poems – on Wikipedia:

I am tired, now I rest,

I close both my small eyes;

Father, let your eyes

Be over my bed!

Otherwise I don’t remember much. Just once, she sat me on the window sill in the bedroom when it was dark and said she would show me the stars in the sky. The room had some brown patterned curtains, and when she pointed out the stars I looked at the curtains and thought that she was pointing at them and saying that they were the stars.

Just before she was moved out, my parents sent me to stay in the home on one of the women who worked in my Dad’s factory. Presumably they feared a scene and thought it would be better if I was out of the way. This woman was called Nelly and at the time she was still single, and living with her mother – there was no sign of a father or anybody else. So I stayed for a while, I’ve no idea how long, probably one or two days, with them in their terraced house in Darwen. All that I can remember is that they were very kind and that the loo was at the bottom of the back garden.

So that’s all I can say about my father’s parents and their generation and the generation before (and my Dad’s cousins and their children, etc.).

So now to my mother’s parents and their families.

My mother’s parents were Rudolf and Helene (née Schubert) Markovits, born in Vienna on 19 Aug 1874 and 17 Sept 1879 respectively. Markovits is the Hungarian spelling; Markovits is a common surname and there are Germanic and Slav variants on the spelling.

In Vienna, when my parents got married on 22 Dec 1932 (so, aged 23 and 22), they could not find/afford a place of their own and so my mother’s parents let them move in with them. So they lived in a top, I think third, floor flat in Hietzingerhauptstrasse 95, in the 13th district (Bezirk) of Vienna. Which means that I lived under the same roof as Rudolf from birth (1936) till when I went to boarding school in 1947; and then during the school holidays, until his death in Jan 1951 and ditto with my grandmother till she died on 1 Dec 1963 (though from about the early 1950s onward, Helene spent several months per year staying with Fritzi. She always went on her own; Rudolf never went. In fact, after arriving in Darwen, I don’t think he ever went anywhere further away than Blackburn, four miles away. So, in Vienna there were my grandparents, my parents, me and the live-in maid, Hilda. I don’t know how big the flat was but I don’t think it had four bedrooms.

Hilda (Weber but referred to a Weberle)) never married and had been my grandparents’ maid since or even before my mother was born. She came from a country village called Stockerau; I went there with my parents and Jimmy, I guess in 1953. By then she’d died but we saw her brother and his wife and he told them about her last years. I don’t remember anything about that. We heard after the war that soon after we’d all left in 1939, some German officials came to ask for us and Hilda was still living there and had the satisfaction of telling them that we’d emigrated. (I was also told by my mother that, while we were still there, some Germans (police?) came with a paper of some sort with my name on it, saying that I was wanted for questioning. When Hilda told them I was a baby, they went away). During that 1953 visit we did not go into our old flat but we visited the flat across the landing, in other words in the same building on the same floor. I think there were just two flats per floor. There was an elderly woman living there on her own called Marie Herzl. She had been there before the war and had known us well. She told my parents all about how it had been there in the war; a very emotional reunion. There was also emotional reunions with the concierge, Frau Kloss, and even the tobacconist on the corner. Everyone whom we saw and who remembered us wept when they saw us.

Rudolf would have turned 65 in 1939, so I would guess he was working pretty well until he left for England. I know very little about him, nothing about his home life as a child, nothing about his education, just nothing at all. Eva may know a bit. I’m told he worked as a salesman for the German electrical company AEG ( = General Electric Company in German). I guess he went round the electrical retailers in and around Vienna, taking the orders they needed to place to stock up their shelves; I think he sold light bulbs, but that’s all I know.

He never had a car nor learned to drive, so he must have got round by public transport. I remember as a child in England that he had one drawer in the dining room sideboard where he kept some bits of stationery which must have been connected with his work; not much, but I remember note pads with advertising at the top, or bottom, for Osram and maybe other light bulbs. And he had some pencils, a ruler or two, but not very much. I remember he has quite a lot of brand new, never been sharpened pencils, some “normal” and some “copying ink” pencils. There wrote like pencils when dry but if you licked the lead, they would write in a sort of purplish colour that evidently was meant to look like ink and to be indelible. (If you google copying ink pencils your find everything you could ever wish to know hundred times over – a wild exaggeration, but depends on how much you may wish to know of course – and photographs of an amazing number of different makes and models).

Some facts from birth, marriage and death certificates (these also give other information such as addresses and professions but so far, I’ve not managed to decipher them as they’re handwritten in the jointed-up writing of the time).

Rudolf Markovits, born 19 August 1874 in Vienna

Father: Jonas Markovits born around 1844. According to genealogieonline.nl he died on September 14th 1909 and was buried on September 17th 1909 in Wenen Zentralfriedhof (Central Cemetery) in Vienna.

Jonas Markovits – Rudolf’s father

Mother: Marie Markovits, née Singer 1849-1914

<JG>According to MyHeritage.com, Marie Markovits had five children by Jonas Markovits, including Rudolf and Edmund. She died in 1914 aged 65. She is apparently buried in Wenen Zentralfriedhof (Central Cemetery) in Vienna.

Helene Markovits, née Schubert, born 17 September 1879

Father:Adolf Schubert

Mother: Franciska (called Fanny) Schubert, née Brandl

(I think the correct spelling is Franziska as on the other certificates, see below, not Franciska)

Their marriage certificate:

Marriage on 3 May, 1904 in Vienna of:

Rudolf Markovits, born Vienna, 19 August 1874

son of Jonas Markovits and Marie Markovits, née Singer

and Helene Schubert, born Vienna on 17 September 1879

daughter of Adolf Schubert and Franziska Schubert, née Brandl

Witnesses: Adolf Schubert and Jonas Markovits

Marriage certificate of Helene’s parents:

Marriage on 1 December 1878 of

Adolf Schubert, born 13 August 1850,

son of Leopold Schubert and Rosalia Schubert, née Fischer

and

Franziska Brandl, born in February 1849,

daughter of Lazar Brandl and Hani Brandl, née Tauber.

Witnesses: Leopold Schubert and Lazar Brandl

Jonas Markovits, born in Budapest (now Hungary), in 1845

Adolf Schubert, born Pressburg (now Bratislava, Slovakia), in August 1850

So, my maternal grandfather was Rudolf. He had, so far as I know, one brother, Edmund Markovits, and two sisters, Karoline, known as Lina, married name Goldschmied, and Franziska? known as Fanni, married name Loewensohn.

Edmund had two sons, Harry and Freddy. They emigrated to Palestine just before the war. Harry and family stayed there after the war, and there may well be their descendants, grandchildren and great grandchildren in Israel today.

Freddy and family came back to Vienna after the war. Freddy and my mother saw a lot of one another as children and always stayed in touch. Freddy was very lively and jolly, like Rudolf.

I met Freddy, his wife Rena and their son Eddie in Vienna from time to time from the 1950s onward. Freddy had a vending machine business, cigarettes and confectionery, I suppose, and became quite well off. Eddie was a bit younger than me, and married to a woman called Evelyn. Freddie carried on working a long time after retirement age to help Eddie with the business. Isabelle and I last saw Freddy and Rena in Vienna in 1992, when we went there for Peter and Lisl’s golden wedding party. At that time they would have been in their early 80s. I never had contact with them after that.

Freddy and Rena got quite well known in Viennese high society, and seemed to have been on friendly terms with quite a lot of nationally known people in politics, business and the arts, opera, concerts, etc. Rena seemed seriously serious and seriously posh.

Lina played the piano very well and was a professional concert pianist.

She had two children, Melita, known as Litty and, I think, a son. The son – I’m pretty sure it was Lina’s son – died of pneumonia in his teens. This is all a bit vague. I remember that my grandmother (Helene), had a black wooden folding rule – I remember it distinctly, at least vaguely distinctly – that had belonged to him. If ever I came home from playing out all hot and sweaty as a child, I was never allowed to have a cold drink, i.e. water, until I’d cooled down, at least if my grandmother was around, because drinking cold water when hot and sweaty was said to have been the cause of Litty’s brother’s fatal pneumonia.

Litty married a Robert Kloss who was not a Jew. Before the war, I seem to remember being told that she was a gymnastics teacher; or maybe I once thought this but was later told it was not true. You’ll have to get Eva to check that. She still has memories of Vienna in the 1930s. The story I heard was that after Austria was annexed, Robert Kloss left Litty and divorced her; and that she was expecting a baby at the time and had an abortion, and then never married again or had children.

More about Litty later.

I know nothing at all about Fanni, but see my comment in part 3, in fact here it is, “I know that one of Rudolf’s sisters, Fanni and family escaped to Canada. Eva told me recently that they got their money out of Austria and were well off, but there was very little or no contact after the war.”

What I want to say now, because after all, I can say what I want when I want in these memoires, is that I really know next to nothing about the childhood or youth of any of my grandparents. I saw my mother’s parents, Helene and Rudolf every day for years and years. Yet I know nothing about them before they they were adults; I never asked and they never said. What a pity!

The only thing I know about Helene is the famous story that she and her sister Paula once decided to get rid of their younger sister Ida by poisoning her. They had heard that the kernels inside peach stones contain cyanide, so they broke open some peach stones, got out the kernels and made Ida eat them. Fortunately for all concerned nothing happened. I know nothing about Helene’s home life, or her school or her friends or her interests, absolutely nothing.

Ditto for Rudolf. He once told me that he remembered that when he was a boy, there were dentists at travelling fairs, and they always (always?) had a man with a drum with them. Then when they pulled people’s teeth out, the drummer banged the drum as loudly as possible to try to take the patient’s mind off he pain.

Once, when I was eleven and had just started learning Latin, he said, “Columba est timida”, (in German, “Die Taube ist fuerchtsam”). Did this mean he had learned Latin?

My mother and later Eva told me that he learned to play the piano as a boy, and he could play easily by ear, but never learned to read music; he just seemed not to want to.

My grandmother once said that when they were young there were still public hangings in Vienna and that Rudolf had seen this.

When Rudolf married Helene in 1904 he would have been 29.

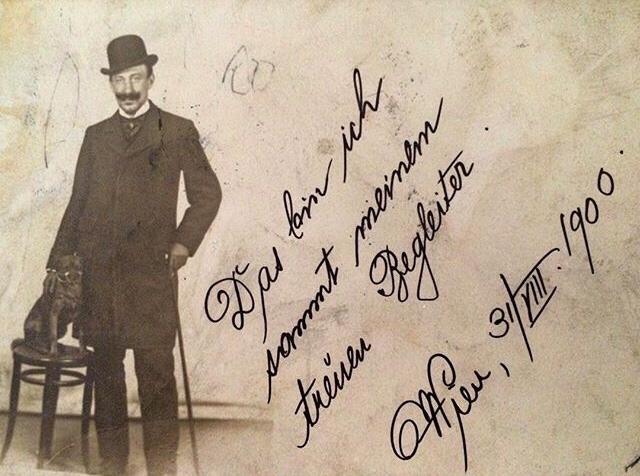

There are a few photographs of him as a young man (which you’ve seen Johnny). There are a couple of him in military uniform so I guess he had to do military service presumably in the early/mid 1890s.

There’s one where he’s dressed very smartly, wearing a bowler hat, with a small dog. On the back, he’s written “Here I am with my faithful companion.” I remember him telling me he had a dog at one time, and I think he said it was called “Koppl”.

When WW1 started, he was just 40, too old to be put into a fighting regiment. My mother told the story that he was in the army pay corps, and at the end of the war when Austria-Hungary had lost and all was chaos, he had a large amount of army pay in his possession. According to my mother he could easily have kept this but he handed it over to his superior officer, who may well have pocketed the lot.

He used to tell the story that after the war, when there was a terrible food shortage in Austria, people used to go to the surrounding farms, begging for food. Then the farmer would ask (in Austrian dialect), “Do you have any sugar?”, “No”. “Do you have any carbide?” “No.” “Then we don’t have any potatoes.”

(Carbide = calcium carbide, used in lamps where there was no gas or electricity).

Another story of my mother’s, which I can’t remember concerned the hyperinflation in Austria in 1923. For some time (weeks/months?) money fell in value by the hour. She could remember Rudolf having huge bundles of banknotes and doing something clever to spend them immediately on goods because these went up in price by the hour as the value of the money fell.

At some time while living in Vienna, he was found to have a non-malignant tumour behind one eye. The eye had to be taken out before the tumour could be removed. So all the time I knew him, Rudolf had one eye and a glass eye, which he used to take out at night from the eye socket. As I child I accepted this as a perfectly normal thing, in no way frightening or horrible. He also had one nostril completely blocked – I’ve no idea of how, when or why.

Eva Schloss has some memories of Rudolf – writing in 2020 she told Johnny:

“Well Rudolf was travelling mostly the whole week for Philips. But weekends they were always with the family. On Sunday morning he always fetched me and he took me along to a pub near the Schonbrunn Palace, where he and his friends would have a Stammtisch (regular table) and I got a soup with cut up pancakes strips. called fridatten.

“When he was home and on the weekend we often slept there and he took Heinz (Eva’s brother) on his lap and told him how to play piano. Helene did look after another relative – I am not sure who she was but it was a very old woman who lived with them but sat in a chair in a small room had to be fed and could not walk. They had this a made called Hilda who did all the housework. Helene went a lot to her sister Ida and Litty and other relatives and visited us also. At her house she had nothing to say it was Hilda who was the boss. But when she came to us which was very often she told my mother how to do everything . We had lots of family and we visited each other a lot .”

And so to Helene, (but see also the family tree p 10), starting with what I know about her but don’t remember, which boils down to her life in Vienna.

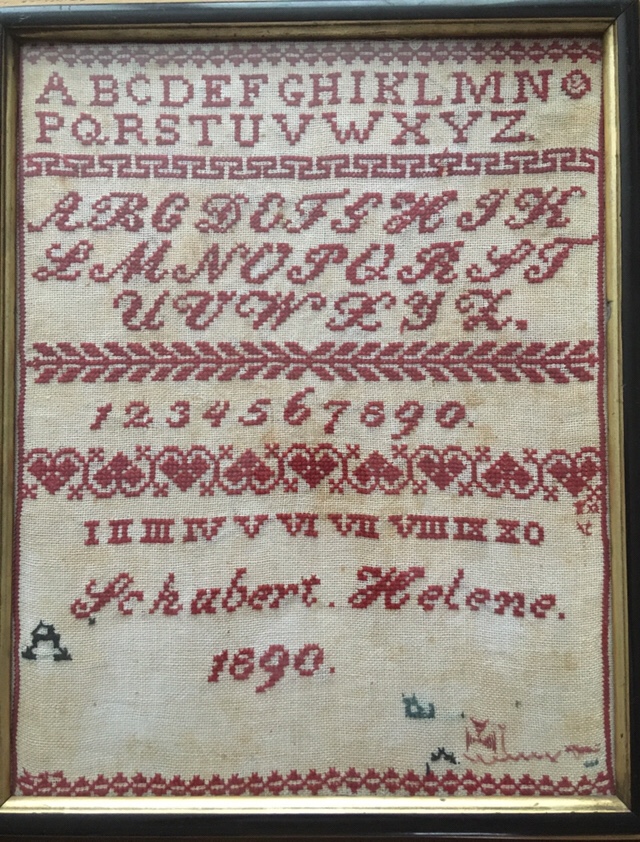

(Tapestry made by Helene in 1890 aged 11)

Again, concerning her childhood and youth, nothing. Just nothing except the story about trying to get rid of Ida by making her eat peach stone kernels. She had the two sisters already mentioned, Paula and Ida and a brother Ernst. I pretty sure that Ernst was the youngest, Ida the next youngest but I’m not sure who was the eldest, Paula or Helene. Helene was born on 17 September 1879 and her parents married on 1 December 1878, nine and a half months earlier, so let’s assume Helene was the eldest. She must have been fond of her parents, Adolf and Franzeska, at least she always had their photographs over her bed in Darwen. Those photographs, two postcard sized head and shoulders portraits, must be around somewhere. (Pictures below)

She and Rudolf got married in Vienna on 3 May 1904, according to their marriage certificate. They had two children, Fritzi, (Elfriede), born 13 February 1905, and my mother, Sylvia Renée, born on 17 June 1910. I think they hired Hilda as their maid soon after they got married; my mother told me that Helene never learned to cook because Hilda always did the cooking, and she (Helene) only started to cook after she arrived in England after 1939. She was 24 ½ when she got married but I don’t know if she ever worked for a living or if she just lived with her parents, (doing what all day?) There is a sampler made by her in existence which hung in a frame in our (my parent’s) houses – Darwen and Maidenhead – and is now with Eva. It’s the alphabet in cross-stitching, not quite complete/fault-free, and dated I think around 1890 (see a picture above).

My mother told me that after the death of the Kaiser, Franz Josef, in 1916, my grandmother was in the huge crowd that followed the funeral cortège. My mother said this was surprising to her as her mother never seemed to show any interest or support for the Austrian royal family.

Her mother, Franzeska, lived with my grandparents after she was widowed; in 1934 she had a fall and broke her femur and this did not heal and led to her death, when she would have been 84 or 85 (so, before I was born). So when my parents got married and moved in with Helene and Rudolf at the end of 1932, there would have been six of them, my grandparents and parents, my great-grandmother Franzeska and Hilda.

What else can I say about life in that flat in Hietzingerhauptstrasse 95? I don’t know if my grandparents moved there when they got married or at a later date. It was always rented.

There was a tram stop nearby; Helene referred the the tram as “die Elektrische” – and I think the tram was the main means of getting around. There was certainly no car; neither grandparent ever learned to drive, and my dad who could drive couldn’t afford a car, though he did have one when he was courting my mother so perhaps he did have one. It was an old tourer, I think a Renault, I even think there’s a photograph of it somewhere. My mother recounted that once they were driving along and my mother saw something moving and called out, “Look a rabbit!”, but it wasn’t a rabbit that she’d seen but one of the wheels of the car that had come off and was overtaking them.

Another story that I heard was that once some silver disappeared from my grandparent’s flat and my grandmother discovered that Hilda had stolen it. I don’t know the details but my grandparents dismissed her and she wept bitterly and begged to be reinstated; after much emotional weeping and begging and promising such a thing would never happen again, she was duly reinstated and all was well.

Another thing I should mention is that Helene suffered a good deal from an ulcer (gastric? duodenal? I don’t know which) over a period of many years in Vienna. Soon after they arrived in England, she had an operation to remove it (in Blackburn Royal Infirmary) and from then on she was completely cured and never had the least problem again.

My grandparents in Darwen

Eva recently gave me the passport Rudolf had when he came to England. It’s a German passport issued after Austria had been absorbed into Germany and no longer existed as an independent country. (It’s stamped with a big red J for Jude).

My grandparents left Vienna to come to join us in England in late 1938. However they hadn’t realised that they needed a Belgian transit visa to go to Ostend to catch the ferry to Dover. So when they arrived at the German-Belgian border, they were sent back to Vienna. Then they organised their Belgian transit visas and this time, in March 1939, got to Ostend and from there to Dover and Darwen.

Quite apart from their history, I should also say a little about what my mother’s parents were like. I must say that I knew next to nothing of their interior life, their beliefs, hopes, fears…

Rudolf seems to have been easy going, the Austrian “gemuetlich”, but I don’t really know. Helene seemed to be a much stronger and more forceful person and perhaps Rudolf had just resigned himself to letting her take charge. He could be very funny and jolly, and this is a real Markovits trait that my brother and I picked up – I’m not sure if you can say inherited. My mother said that Freddy Markovits her cousin also had it.

I remember that my grandparents squabbled quite a lot, but I don’t think it was ever serious or bad tempered. So I shall now close Part 1, which is meant to be about my grandparents and earlier, up to the time when we arrived in England and I began to have memories.

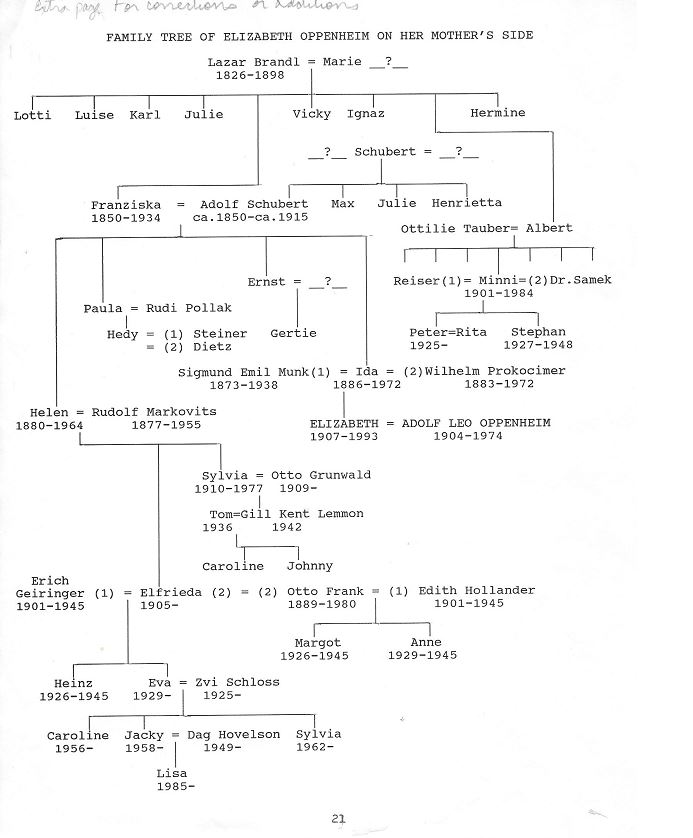

So, this is the family tree in Elizabeth (Lily) Oppenheim’s memoirs. It must have been compiled by her in the late 1980s, Jacky is still married to Dag, but Eric has not yet been born. It must have been completed after Lily died in 1993, probably just with the addition of the year she died. (In her memoirs she says she incorporated the family tree in Eva’s Story).

As you see it is centred on the family of my grandmother Helene and her sister, Lily’s mother, Ida. From the information on the marriage certificates (see pp. 6 and 7 above) you can add or correct some of the omissions/errors, e.g. Lazar Brandl’s wife, Hani Tauber. I always thought the age order of Helene’s brother and sisters was that Paula was the eldest, then Helene, then Ida, with Ernst the youngest of the four. There are also gaps to fill in; Ernst’s wife was Dorle (Dorothea), who we knew very well. More later.

Other comments, from top to bottom:

Adolf Schubert’s parents names are also on given on p. 6

Minni was one of a lot of brothers and sisters, including Hans who was in the Czech army based in the UK. More later.

Minni’s son Stephan was in the Israeli army and was killed in action in the Israel/Palestine war of 1948.

Ida divorced Herr Munk, Lily’s father a good while before he died. More later.

Helene and Rudolf’s dates are wrong, see above.